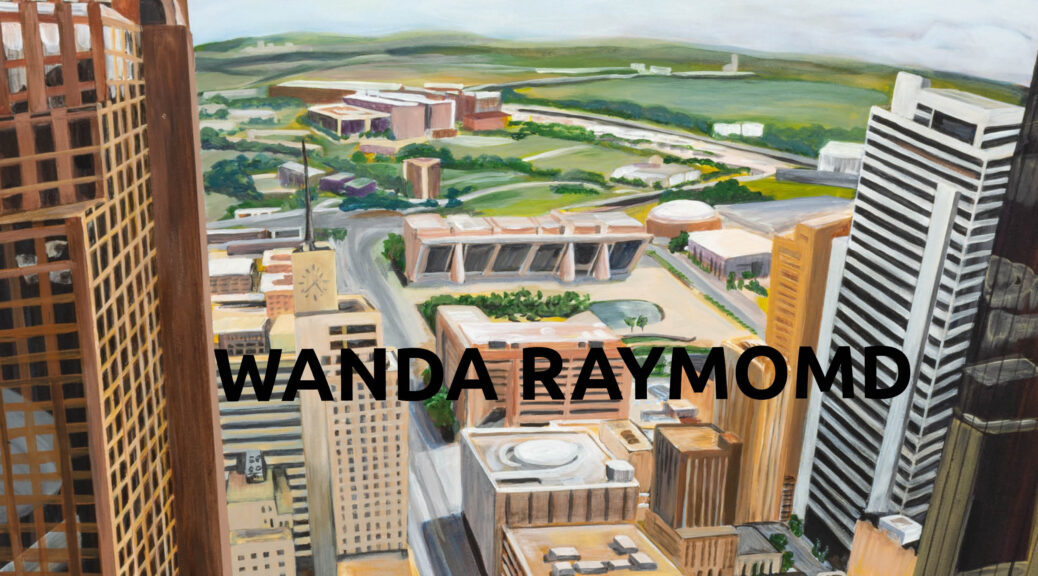

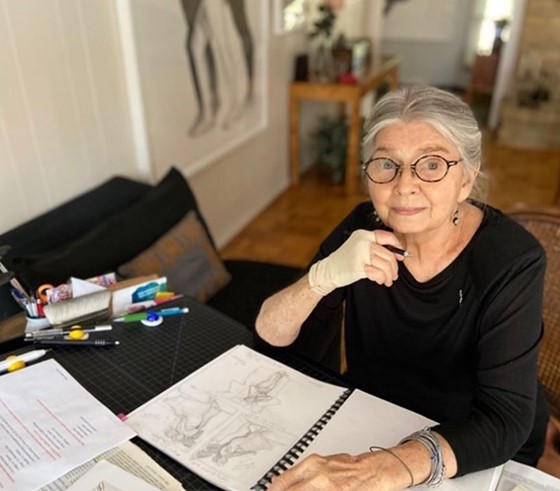

To obtain her master’s degree in painting from Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas, Richardson-based Wanda Raymond had planned to paint the mountains she loved, en plain air, for her final MFA exhibition. But to do so, she would have to make multiple driving trips of over 500 miles to the west and back and incur the expense of multi-week hotel stays and eating out every meal. Realizing the impracticality of her initial concept, she started to search for subjects of similar power and interest closer to home.

As she looked for inspiration, Wanda noticed that the sheer cliffs of glass that formed the canyons and the road rivers that gushed cars between them in downtown Dallas was an interesting alternative. The discovery of this new subject, so close at hand, allowed her to expand her original concept and explore the similarities between a human-made city and a natural mountain range. Through this process, she was able to blur the lines between landscape, and because of her elevated viewpoint, non-traditional still life.

Wanda was born Wanda Abernathy in Washington D.C. in 1935. Her introduction to the power of artwork was when, at age 8, she wrote letters to her older brother who was in a prisoner of war camp in Germany and embellished them with illustrative drawings in hopes of bolstering his morale.

She was 21 when she married Jack Raymond and, to decorate the walls of their new house, she painted what interested her in the neighborhood or while driving through the Virginia countryside. From then on, drawing took a backseat to painting which became her favorite form of expression.

Regarding her love of mountains as subject matter, Wanda Raymond said, “My family moved to Texas in 1979 due to my husband’s job. From then on, my husband and I went to National Parks for vacations whenever we could, and, of course, western parks abound with mountains. They are irresistible when it comes to visual pleasure. I painted every mountain that came into view: Some from a hotel window, some from the top of a cliff, some from the tailgate of the car. I usually started while outside in the fresh air and had to finish, or at least do final touches, inside using a photograph.”

When asked what about downtown Dallas reminded her of the mountains, she said she was, “…fascinated by the views from skyscrapers in the same way I loved the aerial views from mountains. When looking down from a great height, one is overcome with awe, beauty, and possibly even fright. The diagonal slanting lines coming to a point designated by the painter are common to both the mountains and the buildings. Being able to make that designation is a joyful thing.”

Wanda attended Wilson Teachers College in D.C. from 1953 – 1956. She went on to earn a BA in English Literature at George Washington University in 1958. When she felt that her last child was old enough that she could continue her own education, in 1991 she enrolled at The University of Texas at Dallas in Richardson, TX. to receive a Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies. Then, wanting to improve her painting skills, she attended Texas Women’s University in Denton where she received a Master of Fine Arts in Painting in 2001.

Wanda’s cityscapes are quiet and slightly surreal. Highways and streets are almost completely devoid of cars or human traffic as if each was painted when a Cowboy’s home game was underway. It is obvious the buildings are man-made but there is little evidence they are inhabited except for the lights that illuminate some of their windows at night. Like the American painter Edward Hopper, she creates a wonderfully discordant tension in her work that keeps the viewer engaged.

For Wanda Raymond, the discovery of the visual excitement offered by the city became as inspiring to her as her beloved mountains. FAE is honored to be able to offer a selection of Wanda’s powerful cityscapes.

*****

Learn more about the artists whose work you will find on FAE:

WANDA RAYMOND: Paints the City

WANDA RAYMOND: Paints the City

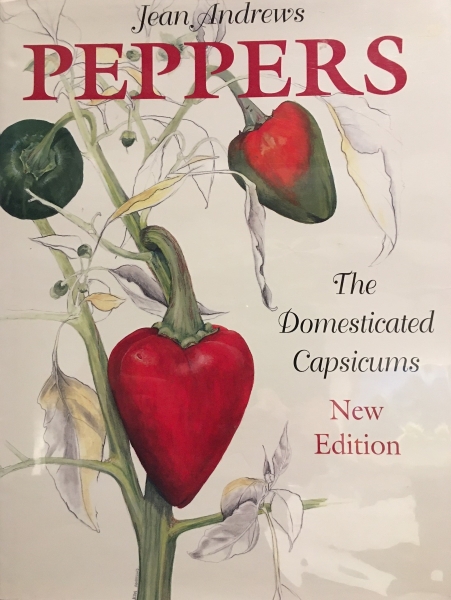

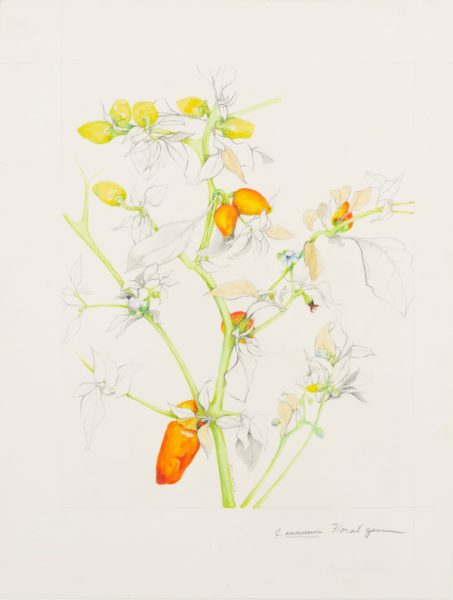

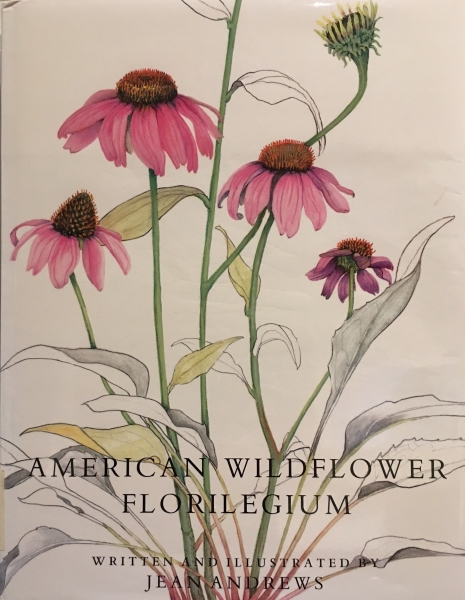

Dr. Jean Andrews, The Pepper Lady

Dr. Jean Andrews, The Pepper Lady

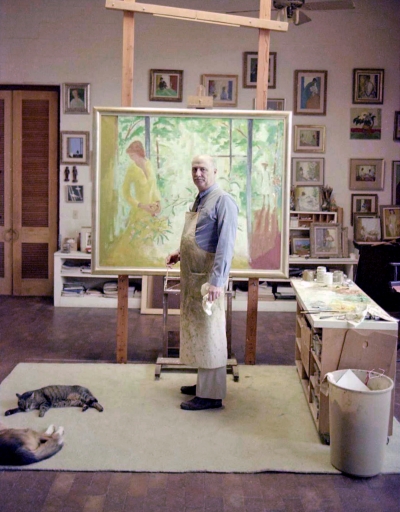

LEE BAXTER DAVIS, A Lifelong Expedition of Discovery

LEE BAXTER DAVIS, A Lifelong Expedition of Discovery

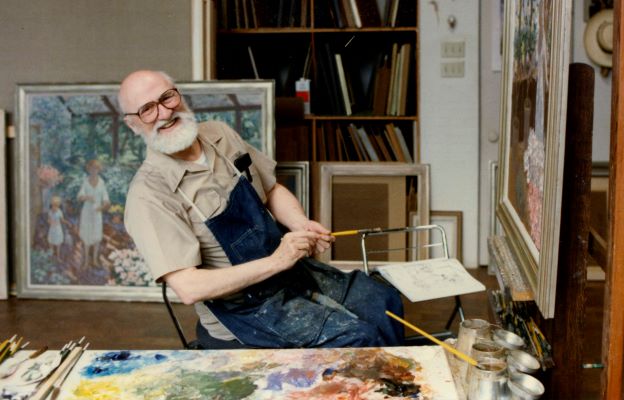

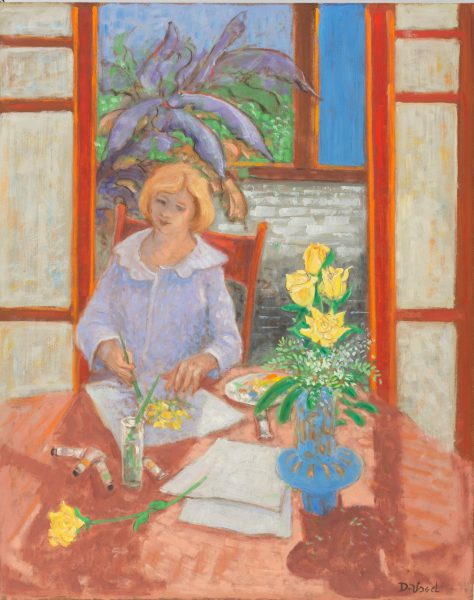

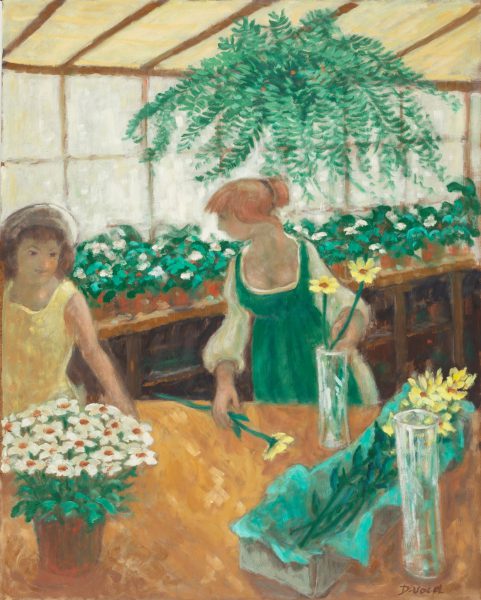

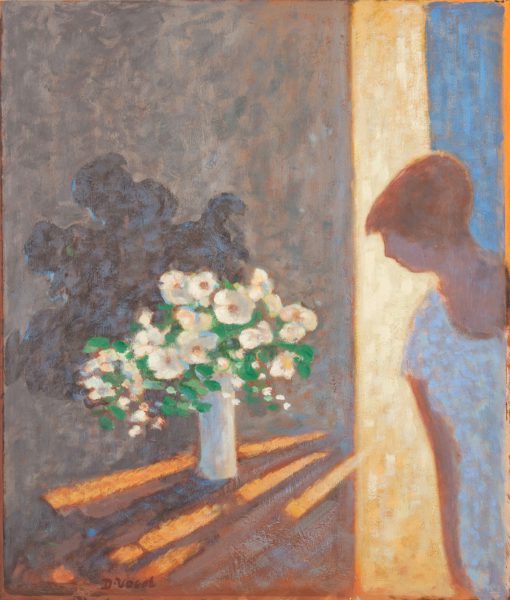

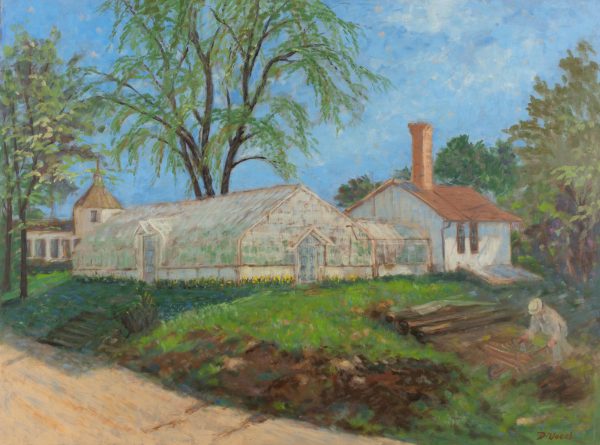

DONALD S. VOGEL, His Philosophy and Studio Practice

DONALD S. VOGEL, His Philosophy and Studio Practice

CHERYL D. McCLURE, Freedom through Abstraction

CHERYL D. McCLURE, Freedom through Abstraction

ELLEN SODERQUIST & Drawing the Nude

ELLEN SODERQUIST & Drawing the Nude

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

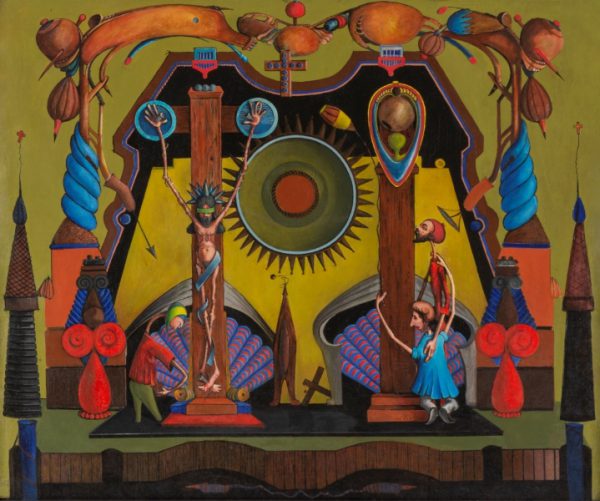

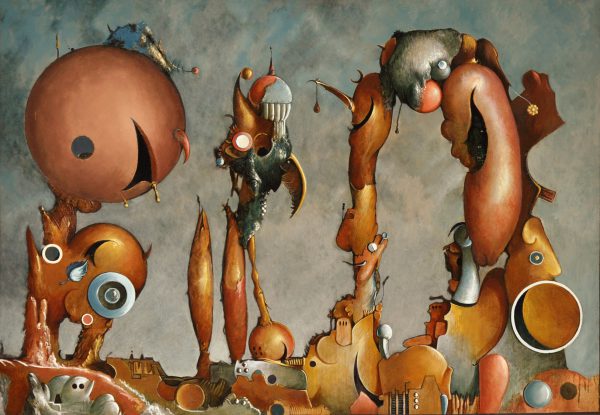

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

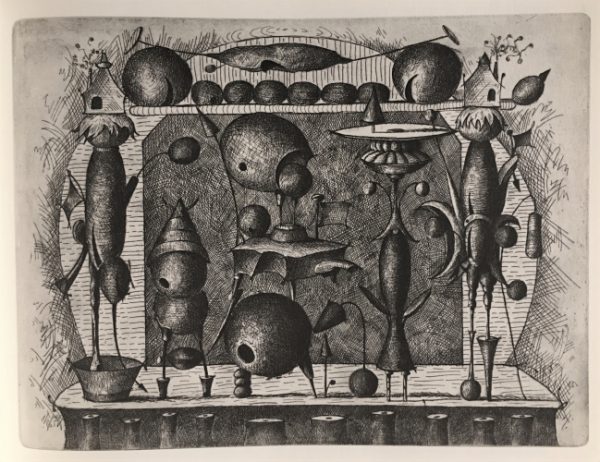

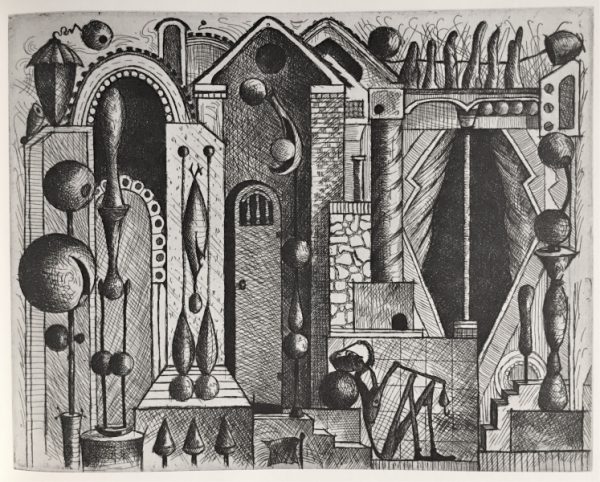

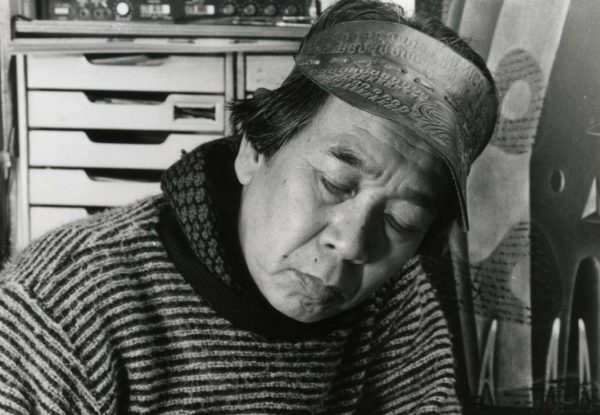

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

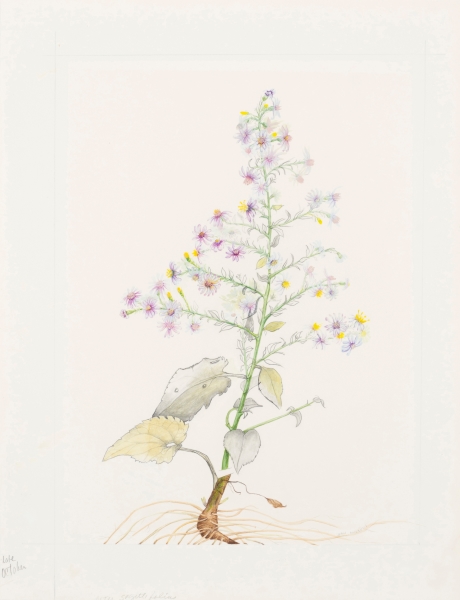

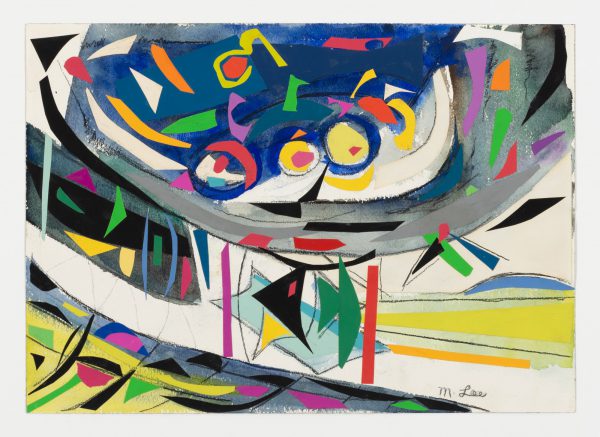

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

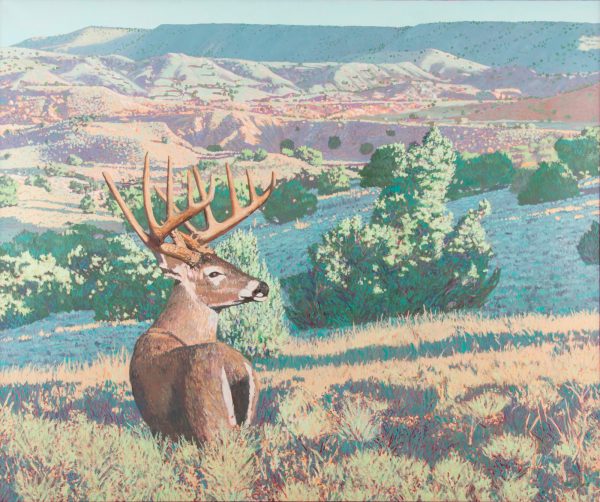

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

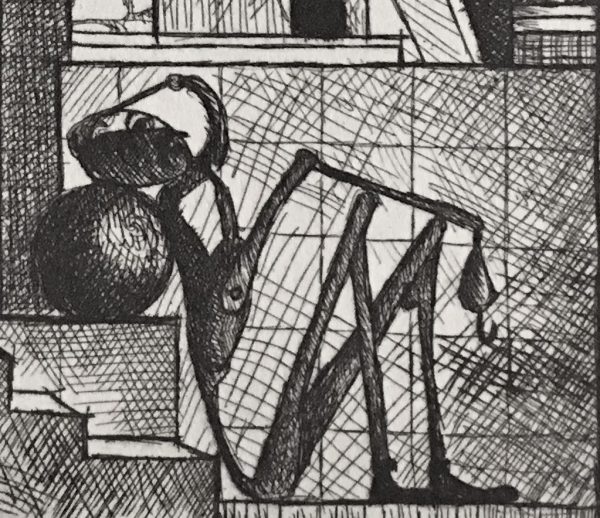

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

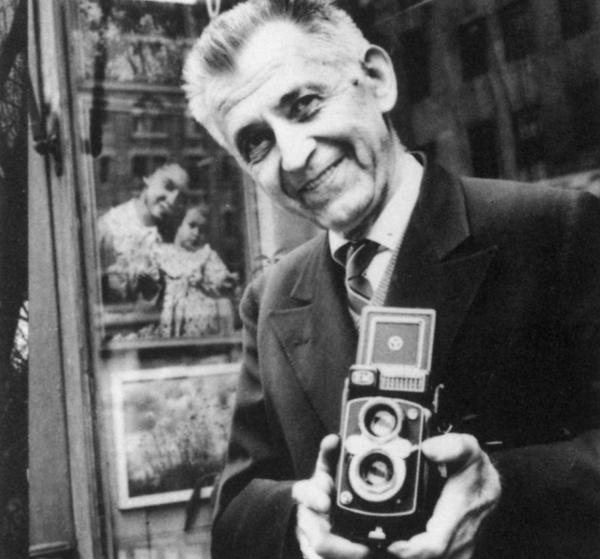

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

*****

To see all available FAE Design Blog Posts, jump to the Design Blog Table of Contents.

Sign up with FAE to receive our newsletter, and never miss a new blog post or update!

Browse fine artworks available to purchase on FAE. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter to stay updated about FAE and new blog posts.

For comments about this blog or suggestions for a future post, contact Kevin at [email protected].

*****