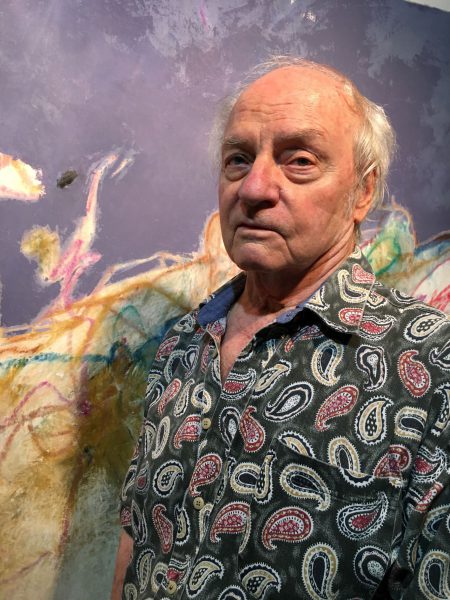

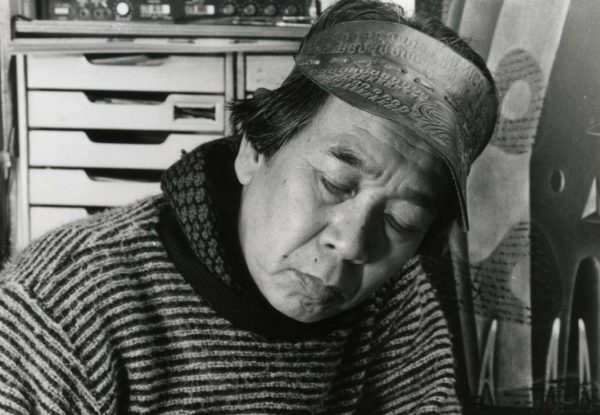

Lee Baxter Davis was born in Bryan, Texas on October 20, 1939. He was raised by his grandparents who were devout Methodists, so going to church was an expectant family activity. When the sermons got a little too long for a five-year-old, his grandmother would offer him paper and pencil to hold his attention. So, from an early age, his drawings were informed by words about heaven and hell. What his grandmother could not have known at the time, was that the combination of the biblical stories he heard, and the drawing materials she had provided, sparked a lifelong expedition of discovery, introspection, and insights he would eventually pass on to generations of art students.

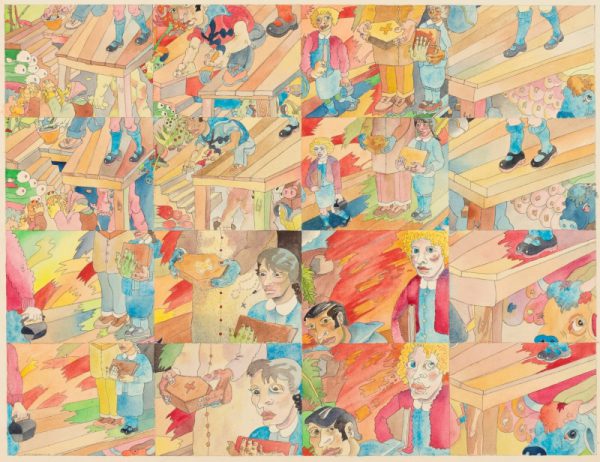

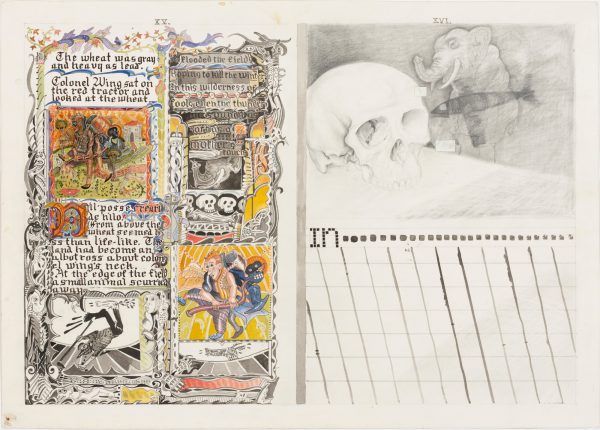

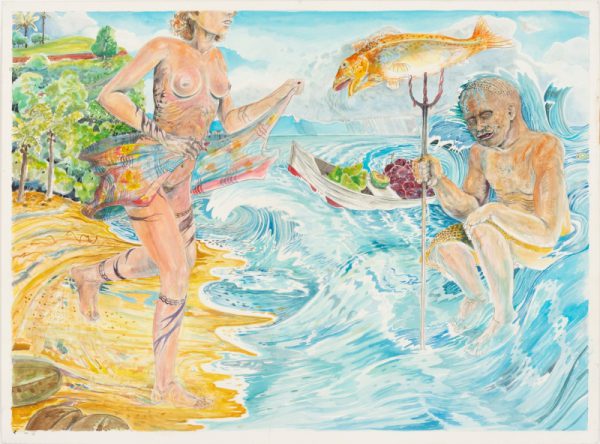

Growing up in rural East Texas towns, Lee’s art library and gallery were the racks of comic books and paper backs in the local drug store. From these, he taught himself rendering and began to create complex and portentous narrative drawings. The subjects of these works were drawn from his imagination and inspired by myth and the origin stories of Adam and Eve and Noah. These early drawings helped to shape the foundation of what was to become his artistic point of view. After graduating high school, he joined the regular army and worked as a medic in post cease-fire Korea where he developed the habit of keeping sketch book diaries.

College and Beyond

After his tour of duty, he attended Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas. Despite initially wanting to be a painter, he continued to focus his attention on drawing, and because of the innate graphic quality of his work, his art teachers urged him to explore printmaking instead of painting.

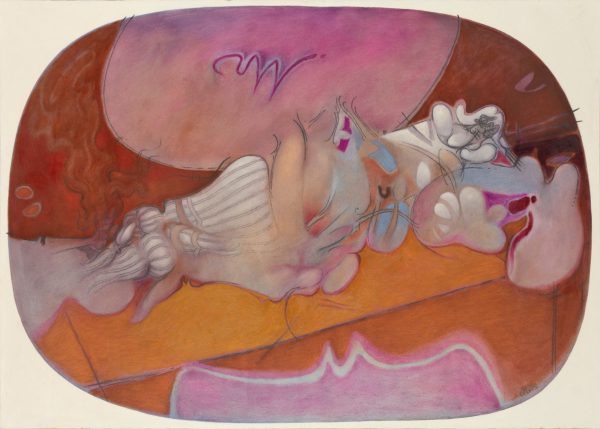

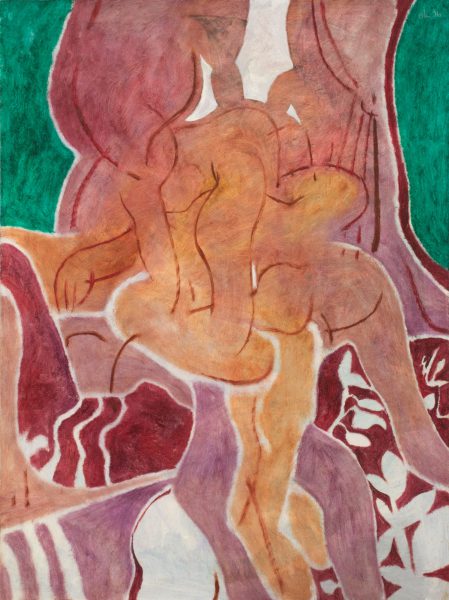

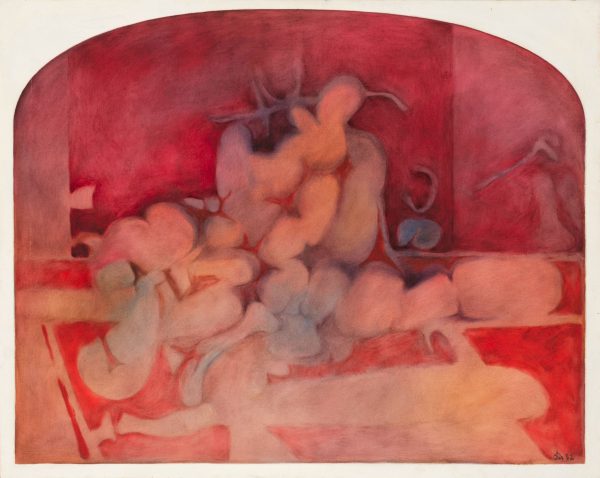

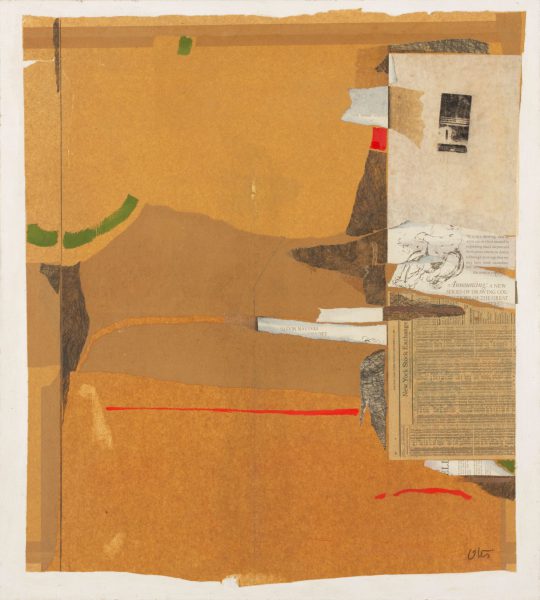

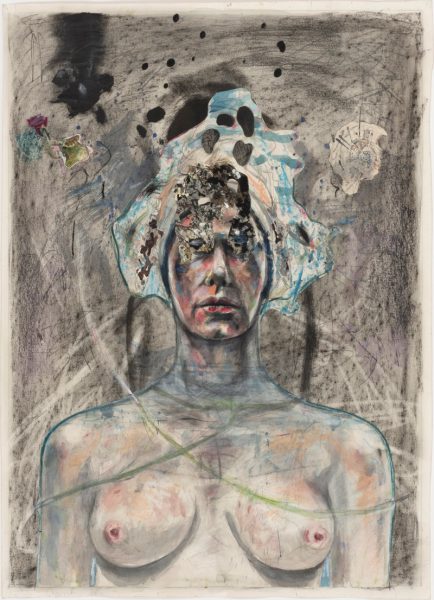

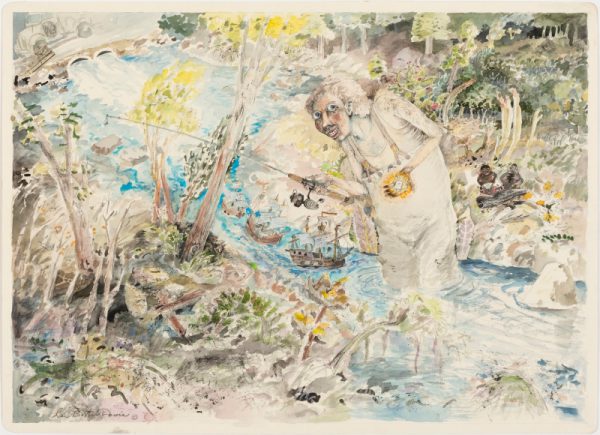

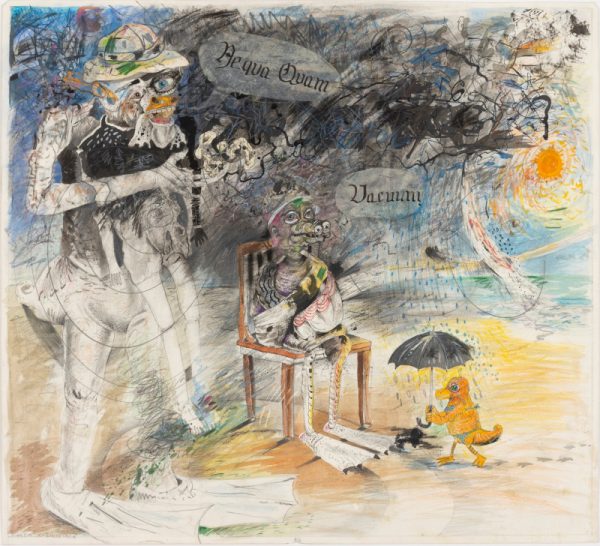

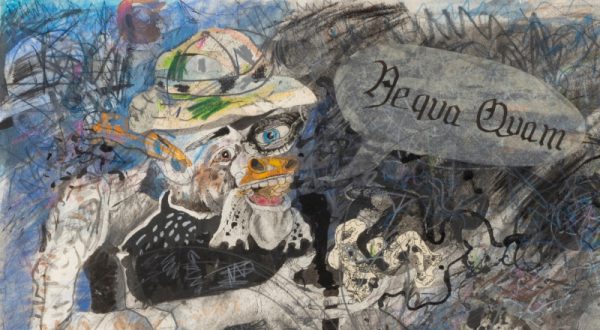

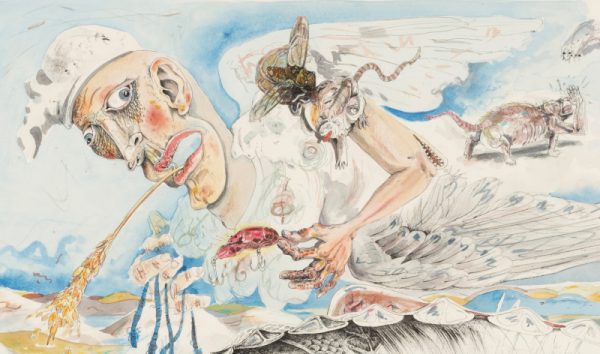

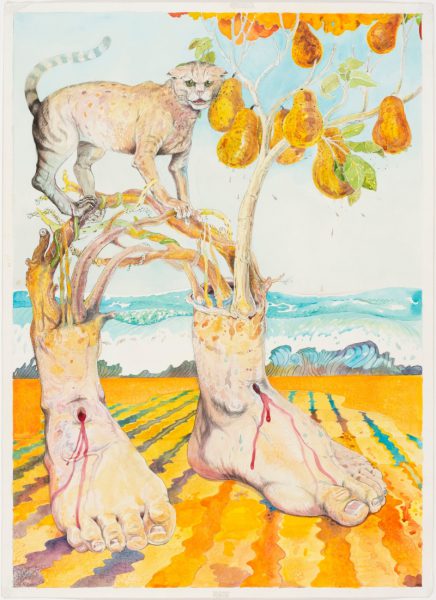

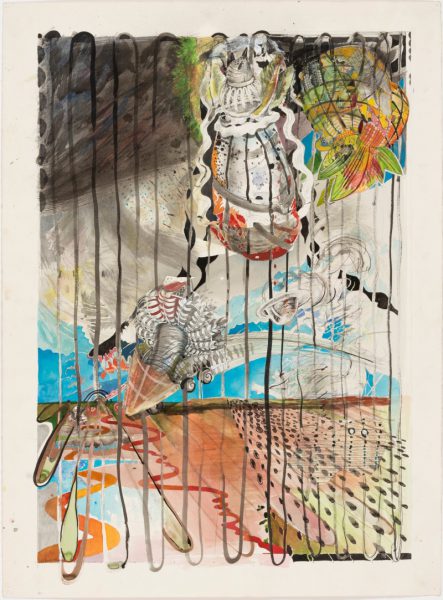

Upon graduating from Sam Houston State with a BS, Lee continued his education at Cranbrook Academy in Michigan where he received an MFA in printmaking. In 1969 Lee took a position at East Texas State University in Commerce, Texas to teach printmaking and quickly added a course in drawing to his teaching load. It was not easy teaching concepts of narrative representational art when the rest of the academic world seemed to revolve around Abstract Expressionism; but, over his teaching career, Lee seemed to have been a magnet for students who appreciated what and how he taught. By 1990, his personal interest in printmaking started to wain in favor of working with ink, pencil, watercolor, and acrylic, because these mediums allowed for more spontaneity and direct access to his, as he calls them, “Psychology Drama Drawings.”

Over time, Lee’s interest in symbolism and religious ritual directed him towards Catholicism. Many of the Biblical stories were the same but the sacramental rituals provided a more complex structure for his temperament and ultimately a more fertile mythology from which to draw inspiration. Having been, from early age, made aware of the protestant view of Heaven and Hell, the mythos of Catholic sacramentality provided a comprehensive visual construct. Lee retired from teaching as a full professor in 2003 to devote more time to his church and studio.

Inspiration:

Early on, Lee would devise ways to develop his memory, visual acuity, and drawing skills. Expressing his point of view regarding memory, he said, “It is remembering, not dismembering, that opens the door to collective memory, the source of all symbol and myth.”

With this construct in mind, he would often look at an object for several moments and then attempt to draw it from memory without reviewing it until he was finished, “to not become image bound.” Lee said that by drawing, “you are teaching your mind to think in contour and line. This allows you to work with your inner eye as well as your outer sight.”

Throughout the early part of his career, unsatisfied with drawing the ubiquitous still life or landscape, Lee would search for unusual ways to generate personal images. While teaching at East Texas State, he was invited to sit in on an English class where many types of unusual story-mapping techniques were discussed. As Lee described it, they talked about a way to generate a paragraph where one randomly chooses a noun, and then made a chart under the noun with 8 lines. On each line, was to be placed 8 randomly created words. Then all these words were to then be combined to create a paragraph. Lee further developed this technique to generate subject ideas for his work, narrative drawings of personally generated mythological events.

All surfaces should be activated into a dynamic, not just balanced composition. This is a fundamental aesthetic. Here in lies the energy of the piece that gives presence to the personal, place and event of the narrative. Dynamic composition makes the work more engaging than just recording of object.

Currently, Lee explores other techniques to manifest new subject ideas, such as his practice of visual meditation, a spiritual exercise of Jesuit origin. Lee explains, “My technique begins with a statement or title. Visualizing in my imagination and interpreting in a drawing provides an entry point into the pictorial space that creates a connection influenced by feelings, dreams, and reality. Inspired by this visualization, I begin by ‘disturbing the picture plane’.”

Studio Practice

Lee will sometimes start by making a sketch or two of an idea, often to scale, and then move on to the mysterious part, disturbing the “pristine psychic window,” the clean white sheet of paper that is tacked to the drawing board on his easel. Once the drawing process is initiated, Lee lets the work take on a life of its own and his job is to “essentially follow it” wherever it may lead, “often moving away from the threshold sutra to the more elusive ‘psychological drama’ of the mythos. At this point further source material taken from sketch diaries may come into play.”

My drawings are compositions of recall. Remembering is putting together an act of imagination that’s origin is found in the architypes.

I asked Lee if he works on more than one drawing at a time. He responded that he is normally working on three; one on the easel and the most recent two tacked up on the wall in order of completion behind him. When he is satisfied with the last drawing of the three, it is removed and the second drawing is moved to the third-place position, and when the final touches are done to the one on the easel and it is judged finished, it is moved to the number two spot and a new “pristine psychic window” is tacked to his easel bound drawing board.

Today, Lee works on hot press BFK (Blanchet, Frères & Kiebler) Rives paper. He says it is not too absorbent so it will hold both an ink line and properly receive a watercolor or acrylic wash. He typically starts with a Black/Warm Universal ink and a graphite 2b pencil, and blenders. Then he will often apply watercolor, both palette and tube, and acrylic paint, mainly white and blue colors, because they can be opaque, and occasionally he will use watercolor pencils.

My art is never objective but always subject. I try to use objects (images) to reveal a subject.

Accolades

Lee’s work can be found in the permanent collections of the Dallas Museum of Art, the Contemporary Museum of Art in Houston, the Arkansas Museum of Fine Art in Little Rock, and the Haas Private Museum and Gallery in Munich, Germany. In March of 2009, he was one of four artists representing the four major geographical areas of Texas in the Texas Biennial in Austin.

Epilogue

In the modern Western Teacher/Student relationship paradigm, it is normal for a teacher and those who know their relationship to think that the student will always live in the shadow of the teacher and will rarely be thought of as their equal or to have surpassed their ability. In ancient China, the Teacher/Student paradigm was almost exactly the opposite. A teacher was considered successful and was venerated when a student surpassed the teacher’s skill level and technical ability. They were expected to push the next generation of artists to exceed their abilities.

Judging by the success of many of Lee’s students, and the high regard they hold him in, years after they graduated, Lee’s impact on their careers has been more than measurable. Time and time again, they show their appreciation by testifying to Lee’s contribution to their ongoing success as artists. In an online announcement of an exhibition of Lee’s work at the Meadows Museum at Centenary College, posted February 6, 2017, there is a quote that reads, California artist Georganne Deen relates a time when a student argued with Davis over whether a work was “good enough.” The student challenged, “If it gets you on the cover of Art in America would it be good enough?” Davis responded, “Depends on whether your motive for making it was to be on the cover of an art magazine or to push the wheel of evolution.”

~~~~~

To see all available FAE Collector Blog Posts, jump to the Collector Blog Table of Contents.

To see all available FAE Design Blog Posts, jump to the Design Blog Table of Contents.

Sign up with FAE to receive our newsletter, and never miss a new blog post or update!

Browse fine artworks available to purchase on FAE. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter to stay updated about FAE and new blog posts.

For comments about this blog or suggestions for a future post, contact Kevin at [email protected].

Learn more about the artists whose work you will find on FAE:

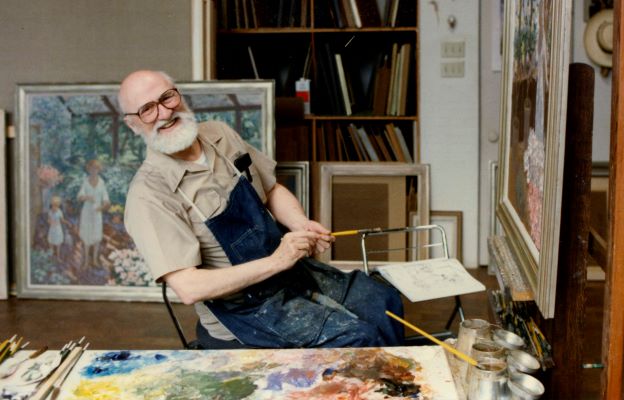

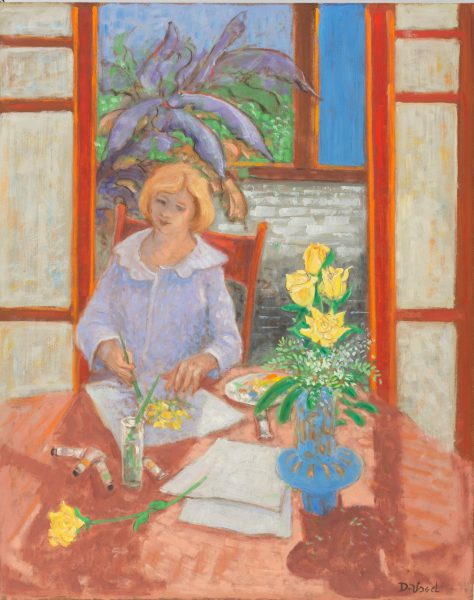

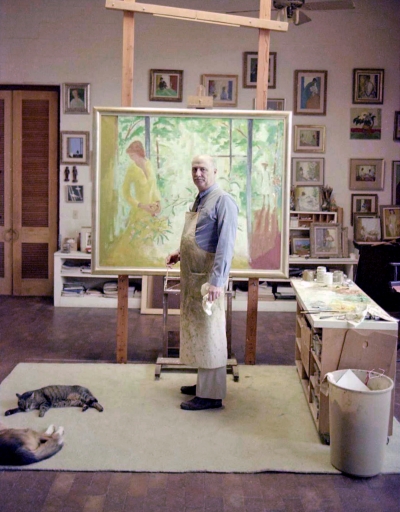

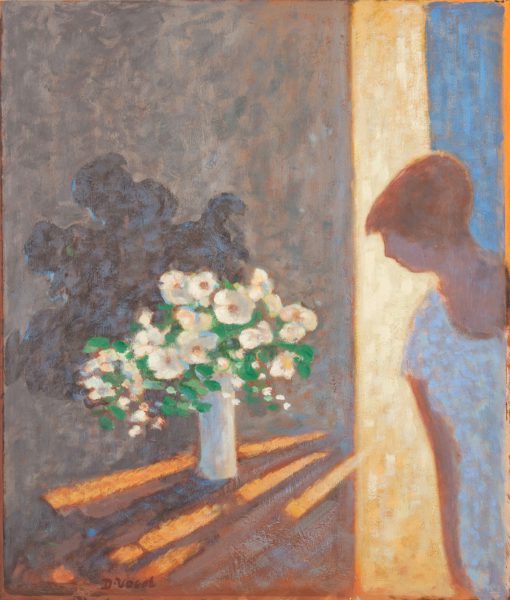

DONALD S. VOGEL, His Philosophy and Studio Practice

DONALD S. VOGEL, His Philosophy and Studio Practice

ECHERYL D. McCLURE, Freedom through Abstraction

ECHERYL D. McCLURE, Freedom through Abstraction

ELLEN SODERQUIST & Drawing the Nude

ELLEN SODERQUIST & Drawing the Nude

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

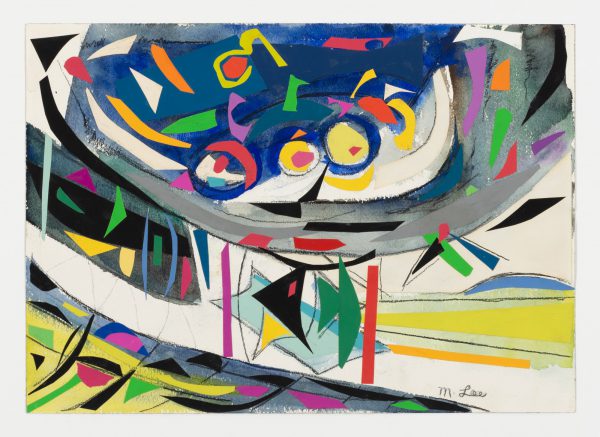

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

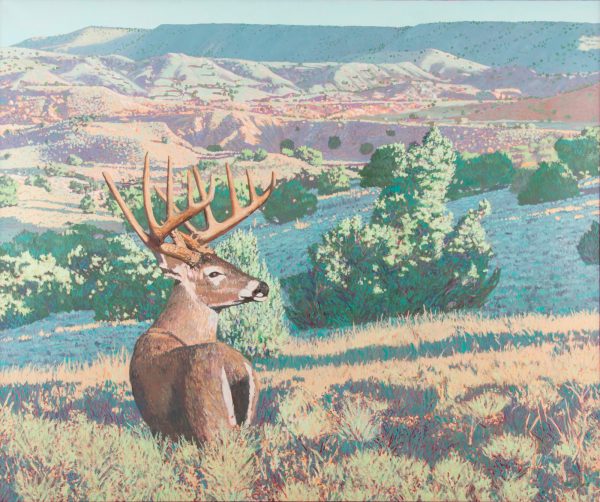

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

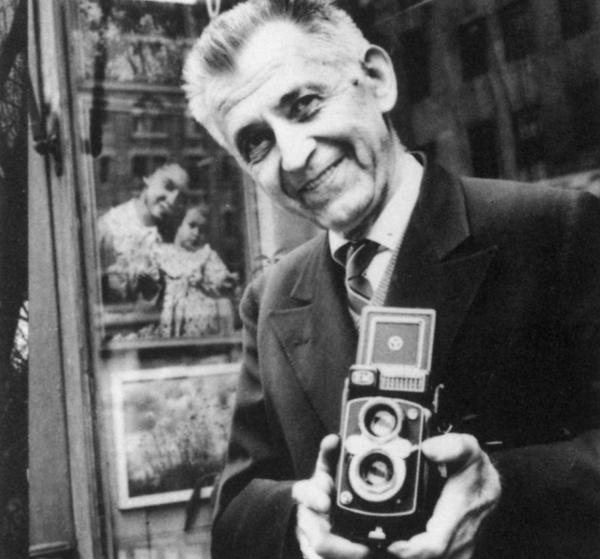

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection