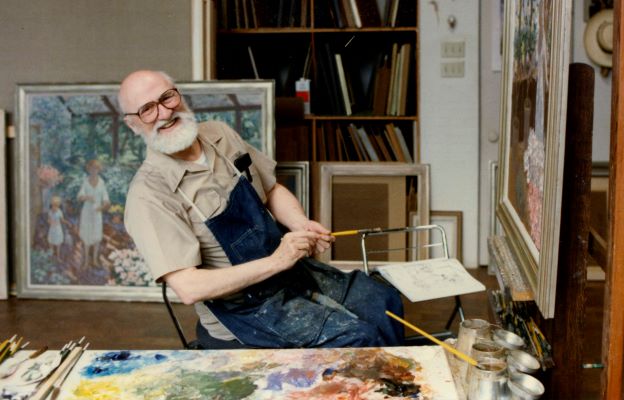

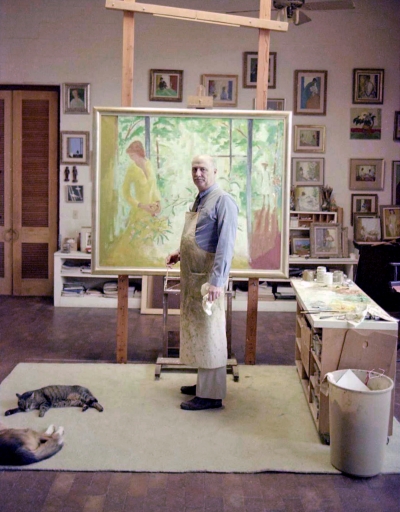

Amongst the literature that is available on the art and life of Donald Stanley Vogel, are numerous articles, reviews of shows, and even an autobiography titled Memories and Images published by the University of North Texas Press in 2000. There is, however, very little information about his philosophy and studio practice. As the middle child of three, I grew up watching him paint and listening to him talk about his work with other artists and friends. So, while his voice and actions still resonate, I though it wise to document what I saw and heard while watching him paint and listening in on his art-related conversations.

Historic Influences

Anyone with a limited knowledge of art history can see that Donald’s style was highly influenced by the French Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists, and with a little more expertise, would include the Nabis and the School of Paris. As a young painter during the Depression, he attended the Art Institute of Chicago and practically lived in their Impressionist galleries. The country was in

the midst of what would later be called the Great Depression and most of his fellow students were painting subjects that reflected the difficult times around them. In contrast, he decided that the art he would produce from then on would lift people’s spirits like the Impressionist paintings he had grown to love.

Using His Imagination

For most of his career, unlike most of the Impressionists, he was a studio painter. He always started a painting with a direction in mind, often generated by a sketchy line drawing of a composition he thought would be challenging. After recreating the important elements of the drawing on a canvas or panel with a burnt umber or raw sienna thinned with turpentine, he would then brush in areas to establish a compositional structure before starting to paint freely with color. But like the subjects he chose, the colors used and how they were employed came from his imagination. Donald often said that he preferred working this way because once you set out to paint something that is in front of you, its presence immediately influences the direction your imagination will take.

Puzzle Master

When Donald stepped up to a new panel on his easel with brush in hand, his approach to painting was to solve a puzzle that had an infinite number of variables and an astonishing lack of rules. He considered the puzzle solved when the imaginary image that then covered his panel had become a “painting.” He defined a “painting” as a work in which the need for another brushstroke, or the removal of a brushstroke, would lessen the artwork’s overall quality. With or without that brushstroke, he said that to his way of thinking, the painting was just a “picture.”

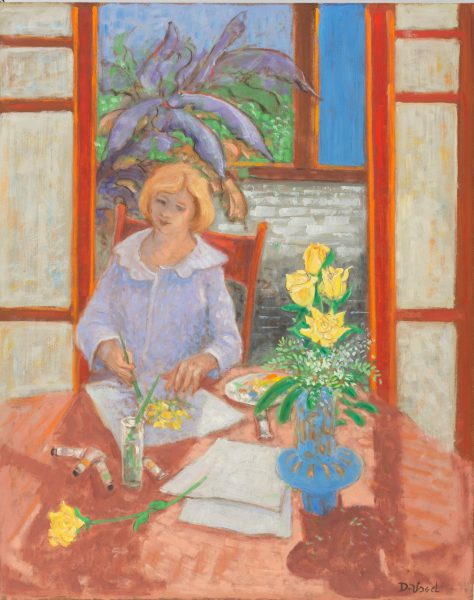

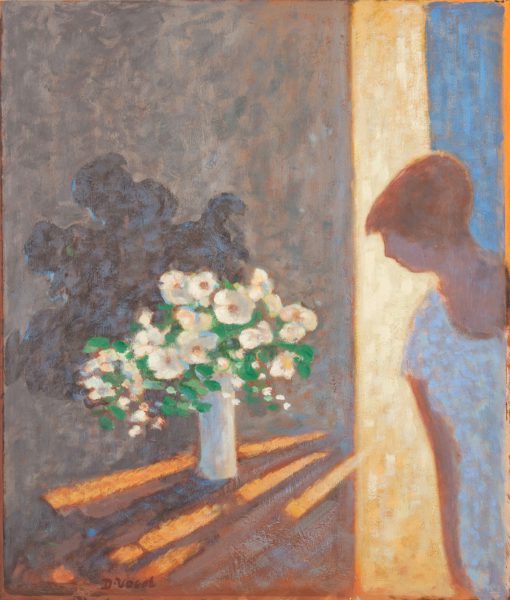

The Figure as a Piece of the Puzzle

Although his paintings were of interiors, still-lifes, and landscapes, the figure, or a group of figures, was a ubiquitous element. To him the figure, as with all other elements, was only there as part of a composition, just another piece of the puzzle to help move your eye through the painting. He also intentionally clothed his figures in generic outfits so that the painting would appear timeless. When asked how he was able to put figures in his paintings without having a model to work from he would say that “after making thousands of drawings of the figure in my youth, it would be sad if I needed to work from life now.”

The Artist’s Palette

Donald derived his colors primarily by tinting white paint. Being right-handed, his white Formica covered palette sat on his right side. At the top of the palette, closest to the easel, was where his containers of brush wash (turpentine) and stand oil were located. Just below that was a heaping mound of white paint. He would drag a dollop of white out into the middle of his palette and then tint it by mixing in the color or colors that were laid out in a semi-circle around palette’s inner edge.

Donald created his own white paint by mixing equal parts of Lead, Zinc, and Titanium. Experience had taught him that each of these whites had positive and negative attributes and mixing them together would limit the negative aspects of each. Throughout his career, he was happy with the results.

Painting in a Frame

Often, especially with larger sizes, Donald would place a prepared Masonite panel in a frame before starting to paint. I learned over time that he normally did this for two reasons.

1. It visually separated the edge of the painting from the chaotic, painting covered wall that was opposite his easel.

2. It steadied the edge of the flexible prepared Masonite panel so it would not bounce back into his brushstroke.

For him, it made painting on panel in his studio easier. For the framer, the linen liners that he used in his frames had to be replaced often because they were usually adorned by errant brush strokes and it was not easy to convince a client that it was a plus that they were getting a free hand-painted liner with their Vogel.

Painting to the Beat

When Donald was painting, there was always classical music playing in the background. He would often talk about how music and the elements of traditional media like drawing, painting, and sculpture were similar. His brushwork was quick and direct and flowed without hesitation between his palette and painting, with a rhythm often in synch with the music that was playing. On numerous occasions he would say that if he had not become a painter, he would have liked to have been a symphony conductor.

A Revelation…

Even though the figure was a constant compositional element in most of Donald’s work, in 1969, a distinct change occurred in how his figures were portrayed. That year, he and his wife Peggy delivered a show of his paintings to the Mobile Art Gallery in Mobile, Alabama. After Donald finished helping install, he asked Peggy if she would like to preview the show alone. After walking through the galleries, she called Donald in to join her and asked him to look around and tell her what was common to all the figures in his paintings. Since it was obvious that he did not see what she had observed, she pointed out that the figures portrayed in each painting were not doing anything, they were just either standing or sitting and idle. From that moment on, all the figures in his paintings portrayed an action.

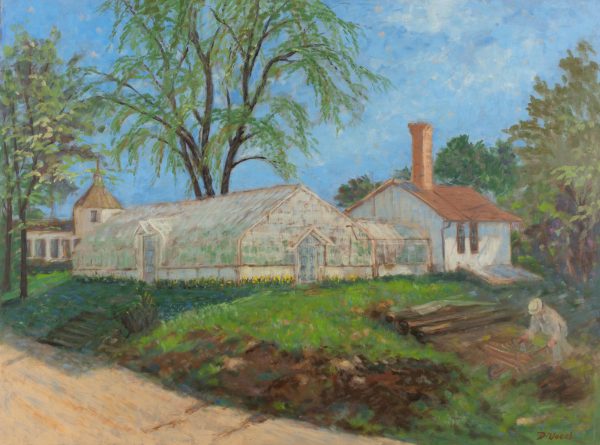

The Greenhouse as Muse

In about 1976, Donald started to explore a subject that was not unique, but one under-utilized by other artists, and as it turned out, perfectly suited his temperament. As a young boy, he worked on an estate outside of Cary, Illinois that had a greenhouse on it. Remembering this unusual light filled space, he executed an imaginary painting of the interior of a greenhouse. He thought it such an interesting subject that he immediately painted several more. This subject provided him with an endless opportunity to investigate the lighting effects the interior of a greenhouse affords. He could explore not only the color and shapes of the blooming plants, but also the light filtering through the whitewashed windows and the visual weight of the moist air proliferating through the space. He could contrast the interior cool light he created with the warm light seen through an open door or window revealing the atmospheric juncture between two worlds. It also afforded compositional opportunities with the architectural structures he imagined that made up the enclosures. The greenhouse became a theme to which he would often return.

One is Not Enough

Donald’s painting career spanned well over 60 years. He was incredibly lucky as a painter because he worked in a style and direction totally of his own choosing and did not have to divert from this path to be successful. The greatest compliment to his legacy is how much his collectors enjoyed living with one of his paintings, often enough to have acquired a second.

If asked by another artist how he handled creating what he considered an unsuccessful painting, he would say, “Never be afraid to paint a bad painting, you learn as much from a bad painting as one that was successful.” He would then say that if he considered a work unsuccessful, it would never leave his studio.

Technical Notes:

Preparing a Support

Until 1945, most of Donald’s early work was painted on canvas. Between 1945 and 1975, he slowly shifted from using canvas as a support to painting on Masonite panels. From then on, most of his paintings from the 48 x 60-inch size size and smaller were painted on panel. With only a few exceptions, larger works were painted on canvas for practical reasons.

He liked working on Masonite because it was a hard surface to work against and it was easy to handle, store and was puncture resistant. Since Masonite is dark in color, he liked the idea of working from dark to light rather than light to dark as is often done when painting on a primed canvas. He even incorporated the dark of the Masonite into his paintings on occasion.

After cutting a Standard Masonite panel to size, he would sand the smooth side of the panel with #80 grit sandpaper in a vertical, and then horizontal direction cutting into its surface to give it a tooth that would hold the paint. (He would never use Tempered Masonite because it was soaked in oil as part of the tempering process, and from experience he had discovered that oil paint would not adhere as well.) He would then seal the panel with Orange Shellac thinned with Methanol by approximately 50-60%. This would keep the oil in the paint from absorbing into the panel and turning the pigment matte. The Shellac would dry quickly, and the panel was ready to go in an hour. (I would personally also recommend shellacking the back side of the panel. This would slow down the panel’s absorption of humidity that could make it sensitive to warping.)

Standardized sizes

Masonite comes in 4 x 8 sheets and Donald would cut the sheets into the optimum number of sizes to maximize using an entire sheet. To this end, the sizes he chose to use were standardized into 8 x 10, 10 x 12, 16 x 20, 20 x 24, on up to 48 x 60 inches. By using a size standard that suited his work, he was able to reuse frames whenever he wanted.

*****

Other Artist Blog Posts:

CHERYL D. McCLURE, Freedom through Abstraction

CHERYL D. McCLURE, Freedom through Abstraction

ELLEN SODERQUIST & Drawing the Nude

ELLEN SODERQUIST & Drawing the Nude

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

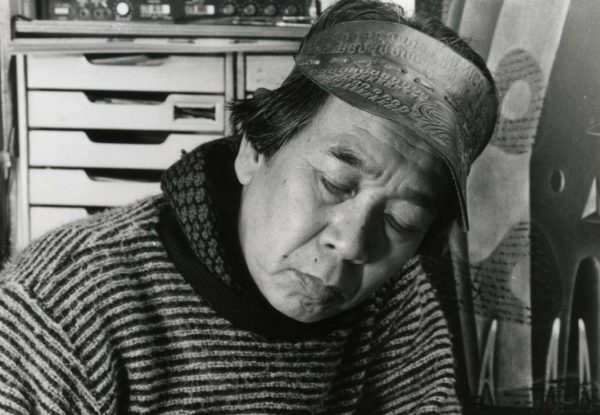

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

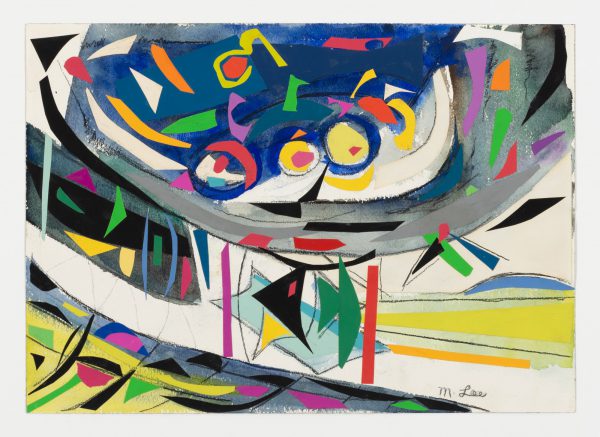

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

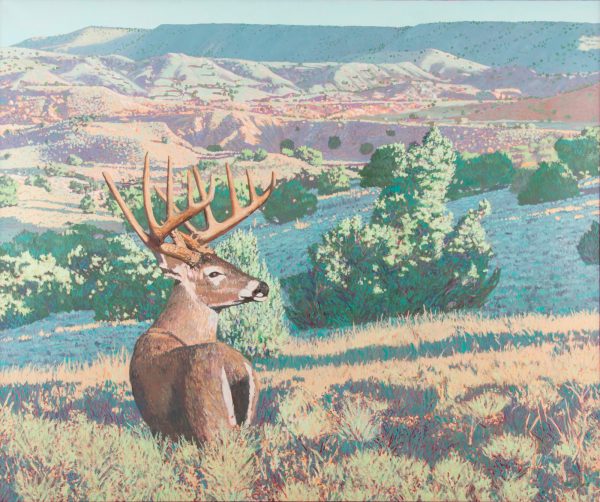

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

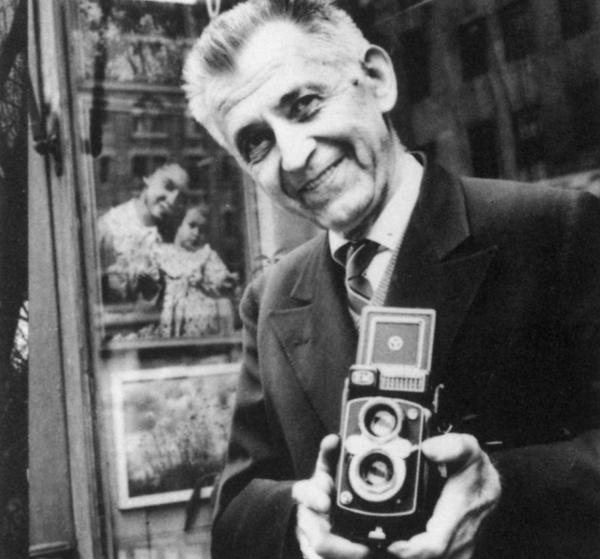

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

To see all available FAE Collector Blog Posts, jump to the Collector Blog Table of Contents.

To see all available FAE Design Blog Posts, jump to the Design Blog Table of Contents.

Sign up with FAE to receive our newsletter, and never miss a new blog post or update!

Browse fine artworks available to purchase on FAE. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter to stay updated about FAE and new blog posts.

For comments about this blog or suggestions for a future post, contact Kevin at [email protected].