TEXAS’ MOST CELEBRATED MODERNIST

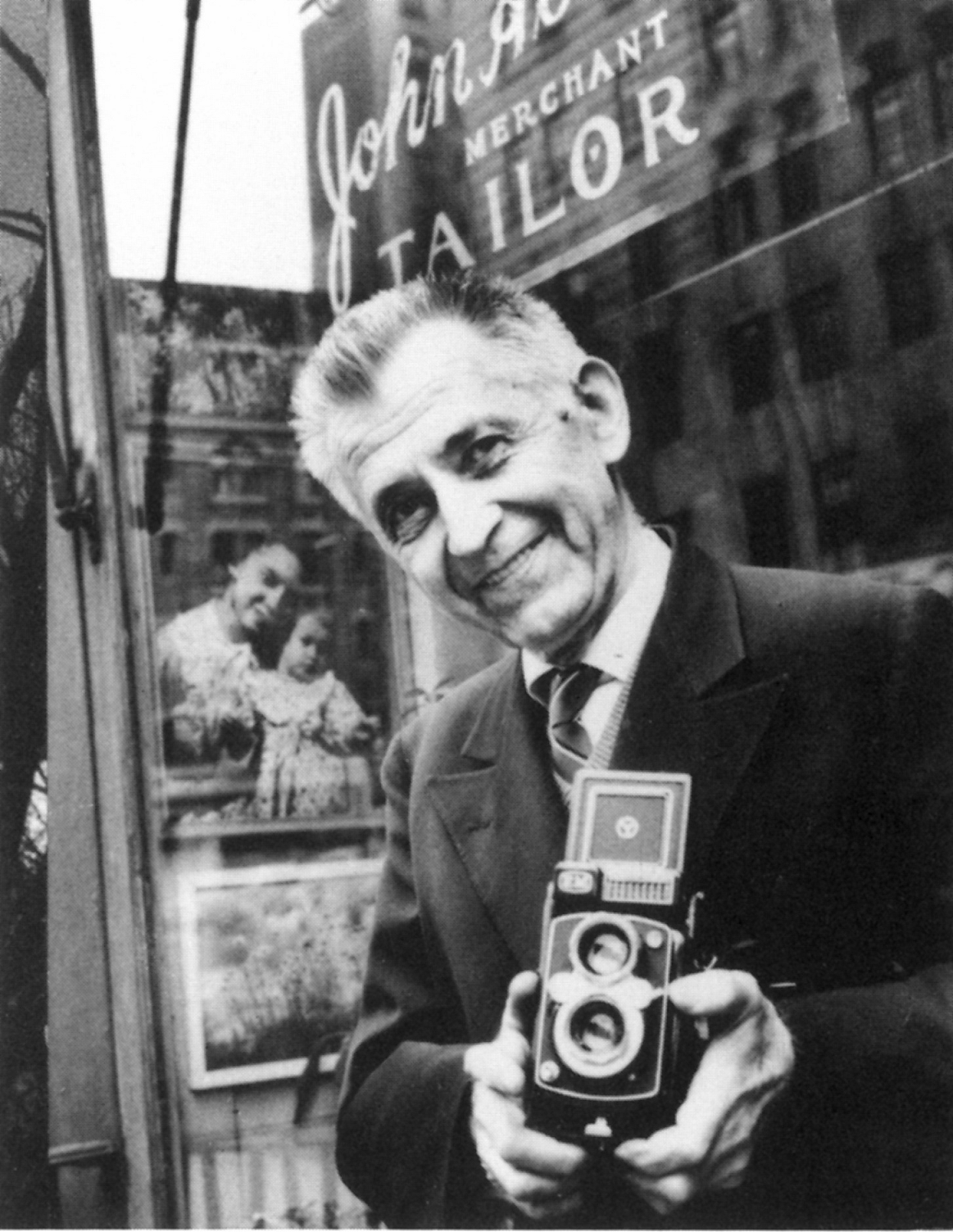

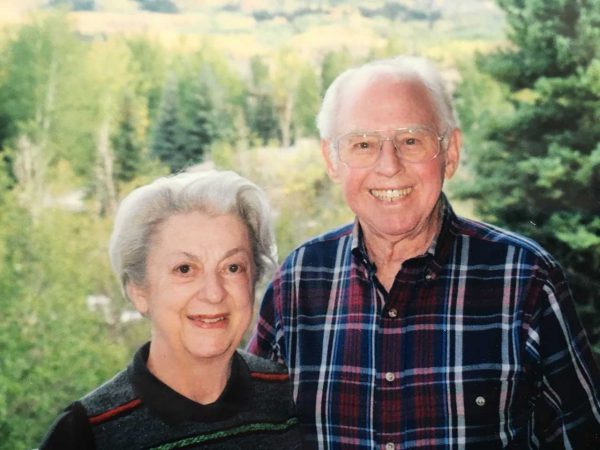

FAE is excited to have a selection of drawings available from the estate of Texas’ most celebrated mid-century modernist painter, Everett Franklin Spruce, consigned from one of his four children, Henry Spruce. Spurce is primarily known for his contributions to the formation of a unique Regional moment that started in Dallas, Texas in 1932.

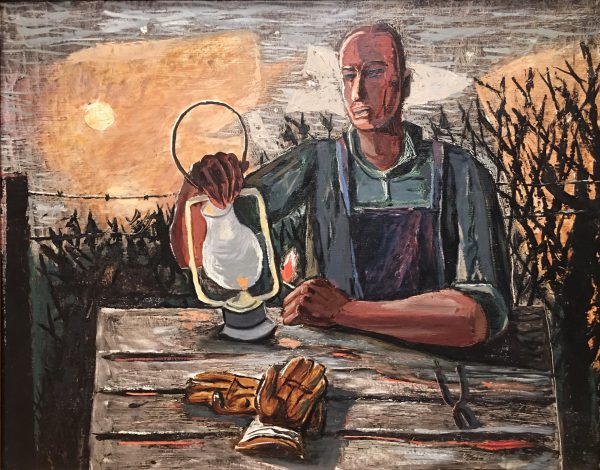

Unlike the Regionalist movement that began in the upper Midwest and focused on the bucolic rural farmlands and farm life that embodied that region, the Texas version took a different approach, focusing on the effects of improper land management that ultimately caused the dust bowl. It was also a broadly based movement that was taken up by many Texas novelists, playwrights, choreographers, and most all other artistic disciplines.

Early Years:

Everett Franklin Spruce was born in Holland, Arkansas on December 25, 1907. When Spruce was 4 years old his father moved the family to Adams Mountain in Pope County and then later to Mulberry, Arkansas, where Spruce attended high school. Spruce showed artistic talent during these early years, primarily in the drawings he did of the Arkansas landscape. His abilities were called to the attention of noted Dallas painters Olin and Katherine Travis. The Travises had established the Dallas Art Institute in Dallas and had summer painting camps in Arkansas’ Ozark mountains. Hearing about this young prodigy and recognizing a burgeoning talent, they offered him a scholarship at the Dallas Art Institute. Spruce moved to Dallas and studied at the DAI from 1926 – 1929 with Travis and another Texas artist, Thomas M. Stell, Jr. In 1934 Spruce married Alice Virginia Kramer, a young woman who was also taking classes at the art institute.

In 1931 Spruce took a position as gallery assistant at the Free Public Art Gallery, renamed the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1933, and was promoted to registrar in 1936 when the museum opened its doors at its new location in Fair Park as part of the Texas Centennial Celebration.

In the early 1930’s, Spruce became one of Texas’s premier Regionalist artists. He quickly developed a national reputation. He was invited to show his paintings in exhibitions across the nation including the Kansas City Art Institute (Kansas City, Missouri); the Rockefeller Center (New York, New York); the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, New York); the Palace of Fine Arts (San Francisco, California); and the New York World’s Fair Exhibition (New York, New York).

His Years Teaching Art:

In 1940 Spruce, with only a high school education, joined the art faculty at the University of Texas at Austin where he began as an instructor in life drawing and creative design. From 1949 – 1951 Spruce served as Chairman of the Department of Art, and in 1954 he was promoted to the position of Professor of Art. In 1958 Spruce was the first artist featured in the Blaffer Series on Texas Art, published by the University of Texas Press. The portfolio, titled A Portfolio of Eight Paintings, includes the essay “Everett Spruce: An Appreciation” by Jerry Bywaters, then director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts. Spruce was also honored by the American Federation of the Arts’ offer to sponsor a traveling exhibition of his paintings in many venues throughout the Midwest and Southeast, starting at the McNay Museum in San Antonio.

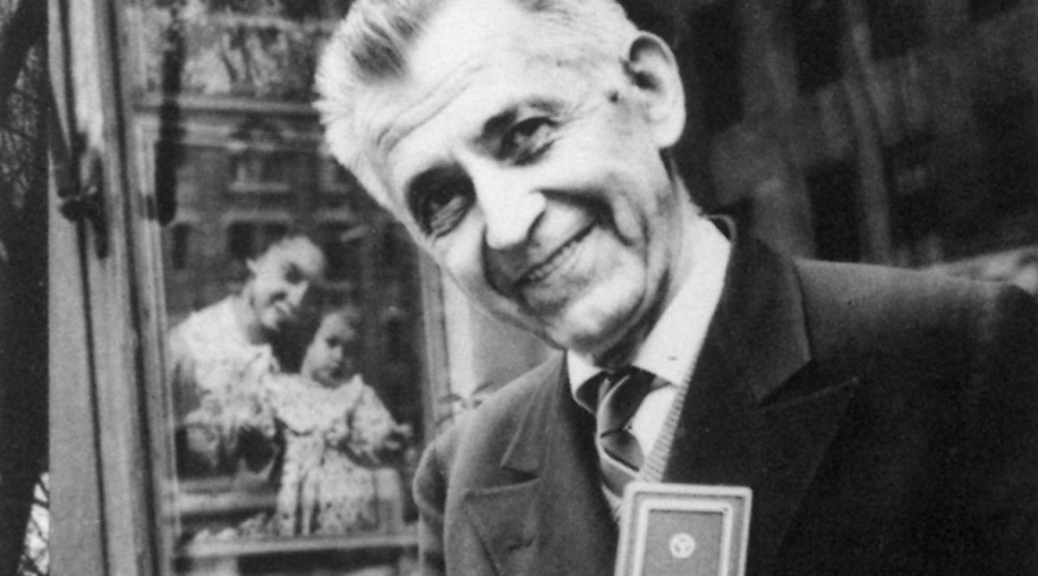

In 1974 Spruce retired from the Art Department as Professor Emeritus, yet continued to paint until he was 88 years old. Spruce died in Austin in 2002 at the age of 94, survived by his twin daughters and two sons. Spruce’s paintings were collected by many of America’s major museums including the Metropolitan Museum in New York; Dallas Museum of Art; M.H. DeYoung Museum in San Francisco; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Phillips Gallery, Washington D.C.; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, to name a few.

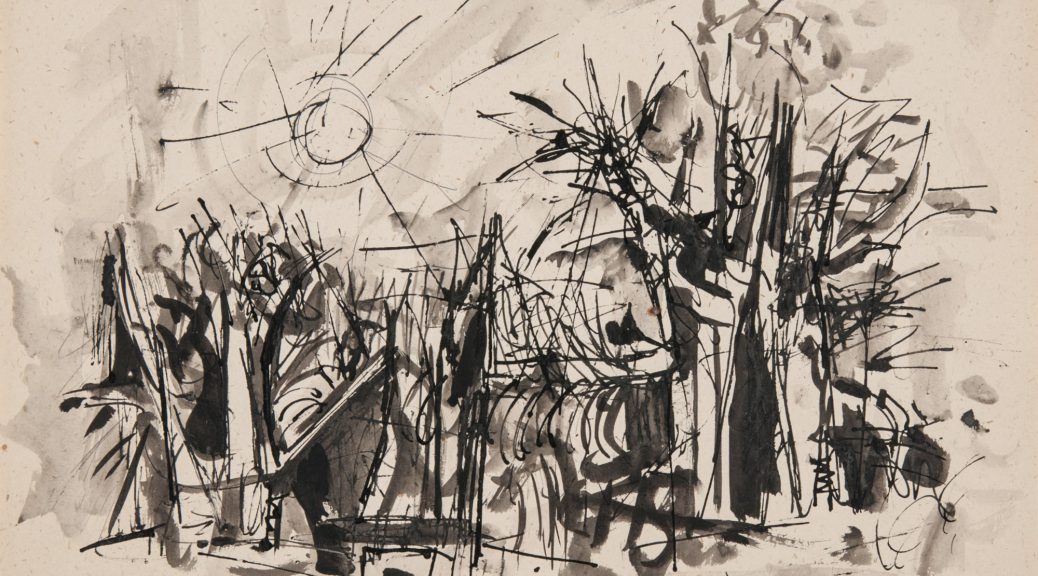

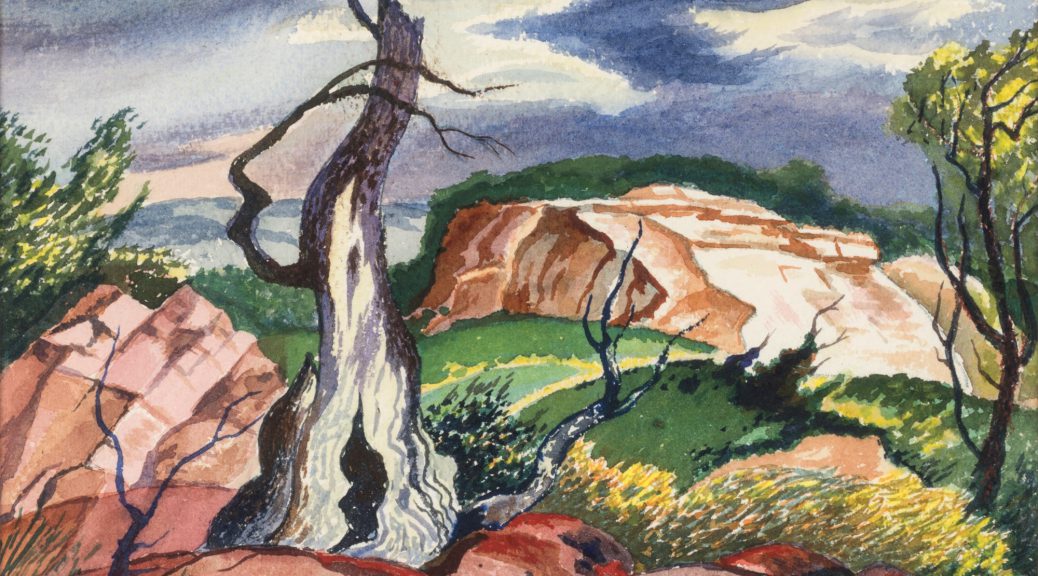

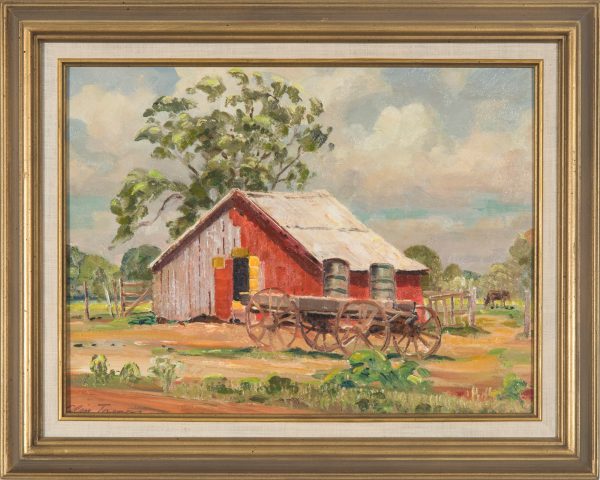

Spruce’s Drawings:

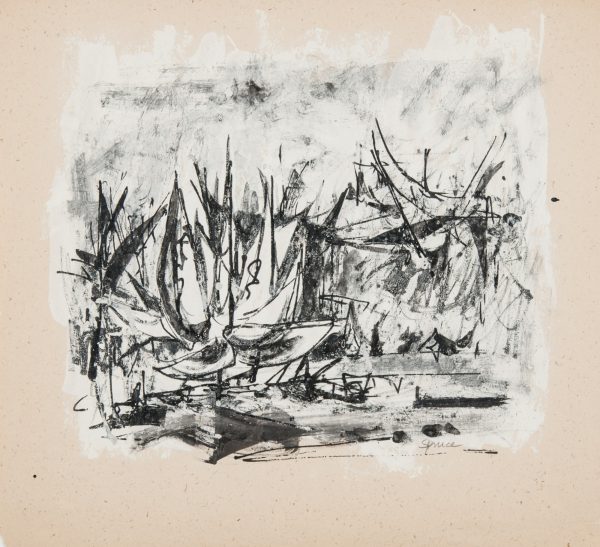

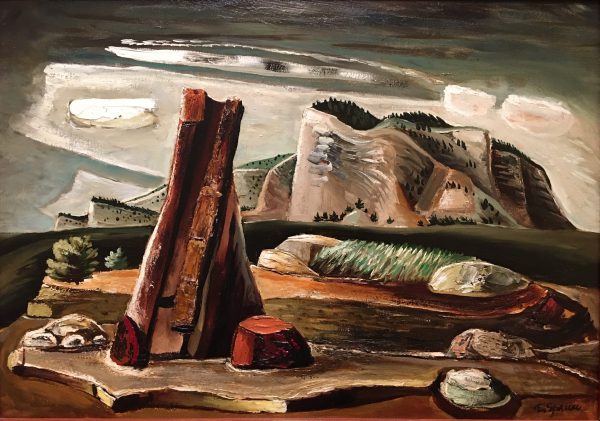

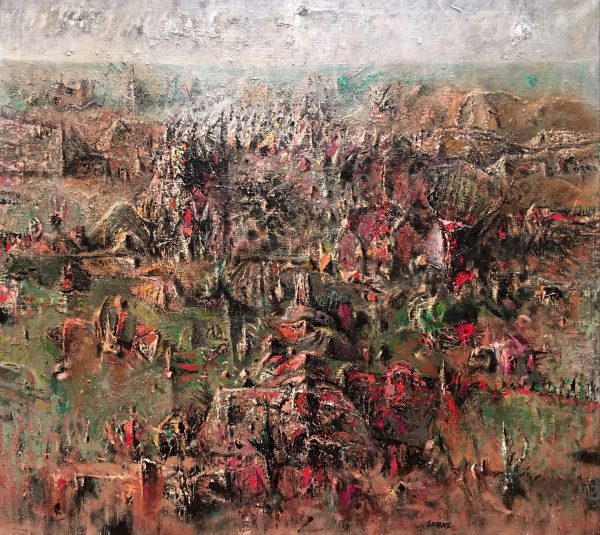

Spruce’s drawings were rarely used as studies for paintings. The vastness and majesty evoked in his paintings serve as a counterpoint to the drawings’ tighter, more detail-oriented focus. He drew inspiration and subject matter for his expressionist landscapes from numerous weekend outings with his family into West Texas, and South to the Texas Gulf Coast. He would pull over to the side of the road whenever something in the landscape caught his attention and, to his family’s distress, memorize every aspect of the scene for 15 minutes or longer. From these memories of place, he would create paintings or drawings of these inspiration points in his studio, often months later. He did not work from photographs or sketchbook, letting his memory serve as reference.

Spruce’s drawing style became freer as his career evolved, producing increasingly abstract and expressionist works. Even Spruce’s latest drawings show an absurdness of hand and a confidence of purpose. His evocative depictions of Texas landscape have cemented his Lone Star Regionalist status, and stand as a testament to his love of the land.

See all available works by Everett Franklin Spruce.

Texas Made Modern:

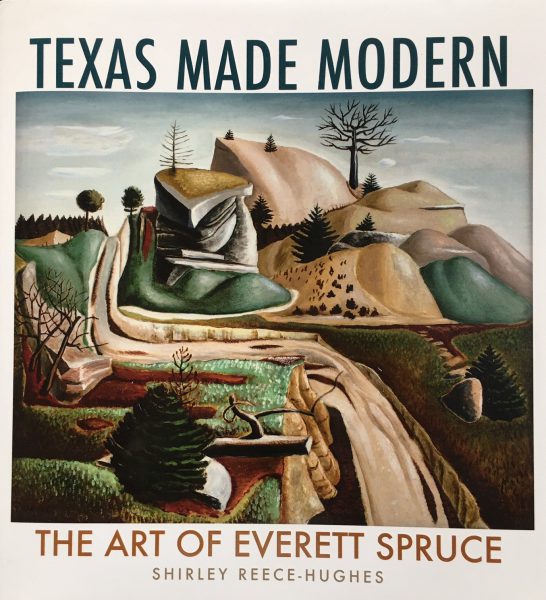

Through November 1, 2020, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art honors Everett Spruce with his first major museum retrospective. The exhibition is titled Texas Made Modern, The Art of Everett Spruce.

The exhibition is thoroughly documented with a fully illustrated catalog co-published by Texas A&M Press and the Amon Carter. The primary essay is authored by the exhibition’s curator, Shirley Reece-Hughes.

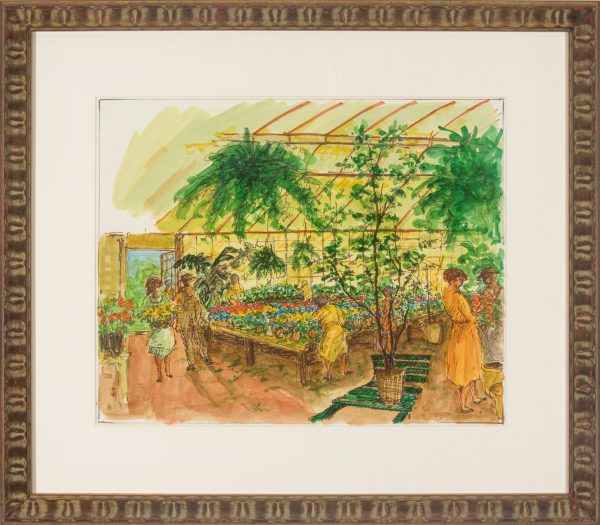

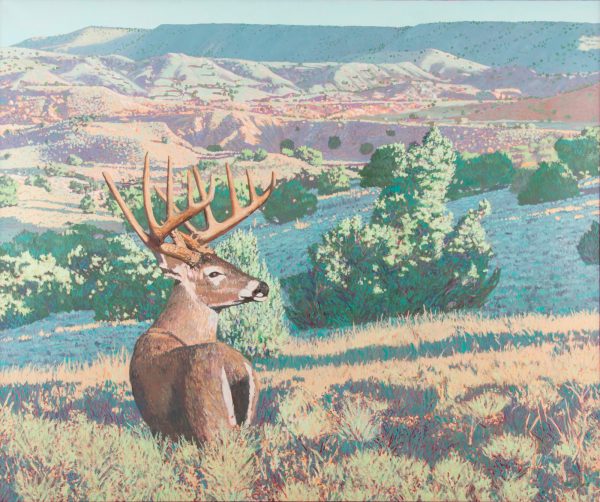

A Few Highlights from Texas Made Modern:

*****

Blogs on other Texas Artists:

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

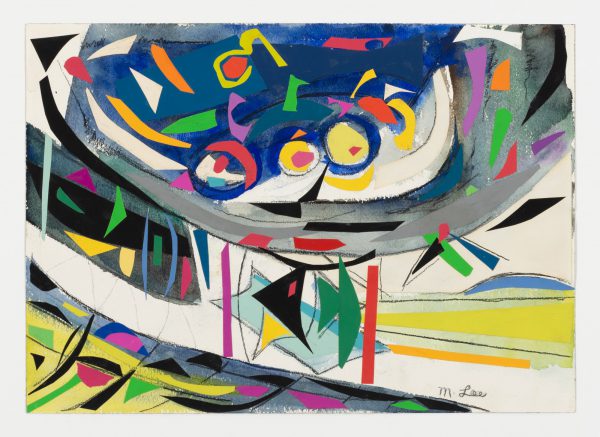

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

M. J. LEE Estate Gifts to the Amon Carter Museum

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

To see all available FAE Collector Blog Posts, jump to the Collector Blog Table of Contents.

To see all available FAE Design Blog Posts, jump to the Design Blog Table of Contents.

Sign up with FAE to receive our newsletter, and never miss a new blog post or update!

Browse fine artworks available to purchase on FAE. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter to stay updated about FAE and new blog posts.

For comments about this blog or suggestions for a future post, contact Kevin at [email protected].