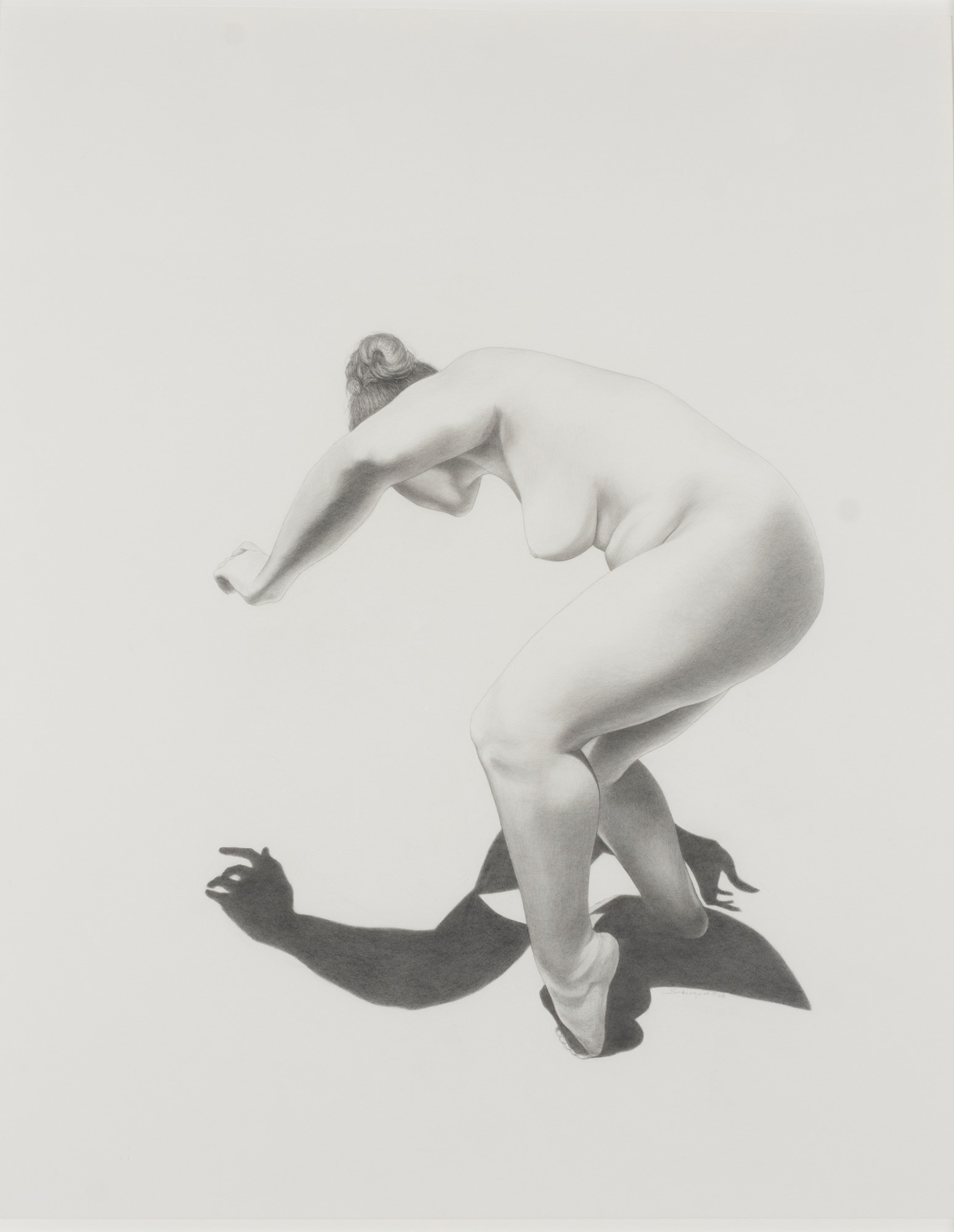

FAE is pleased to offer artworks by Dallas artist Ellen Soderquist. Ellen has been working as an artist since 1973, and has been teaching life drawing classes since 1979. Highly respected as an artist and educator, Ellen is known for her exquisitely rendered and highly developed graphite drawings of the nude figure. She teaches life drawing and lectures on the nude as a form of art explored by artists throughout history.

First Inspirations

Ellen Soderquist was raised in Texarkana, TX, where she showed an artistic inclination from a young age. Because Ellen’s father was a photographer, there was always art on the walls of their home while she was growing up. Along with his photographs, there were also drawings and watercolors by other artists, and they had artbooks in their library. However, her favorite book was not an artbook, it was her mother’s copy of Gregg Shorthand. She told me she “loved looking at that book and all those squiggles. Before I learned to write, I remember writing pages and pages of squiggles.” With amusement, her mother would later read the imaginary letters to her.

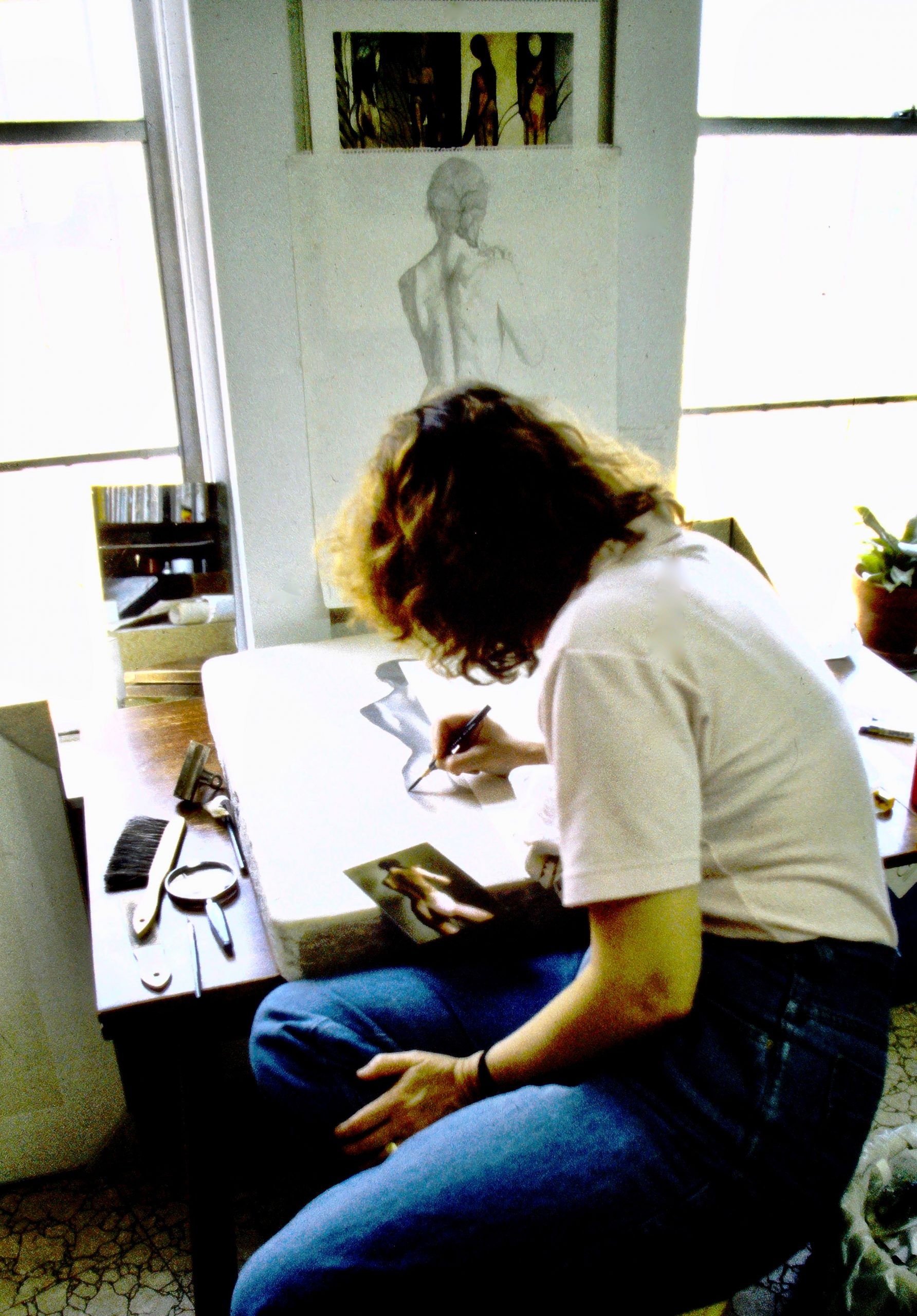

In Kindergarten, Ellen was inspired by one of her teachers who illustrated children’s books. She would often draw her students while they were playing at recess. During naptime, she would let Ellen peer over her shoulder to watch her draw. Watching an artist work made quite an impression on her.

Why the Nude?

Ellen’s first formal art training was at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. Unfortunately, she found her first drawing class, where they worked from still life setups, so tedious she nearly switched majors. It was not until she first started drawing the nude from a live model that Ellen was “hooked.” Even though life drawing was only “taught to discipline and train the eye and hand,” like the still life setups that had totally bored her, she completely embraced the challenge of drawing from the model. She was fascinated with the discovery that “the slightest movement or nuance of pose can change everything.” To Ellen, this was a revelation.

Even though Life Drawing was not emphasized in SMU’s art program, Ellen was intent on pursuing drawing the figure. This discipline was only required for two semesters, but Ellen was able to outwit the Registrar by finding a way to take a life drawing class every semester.

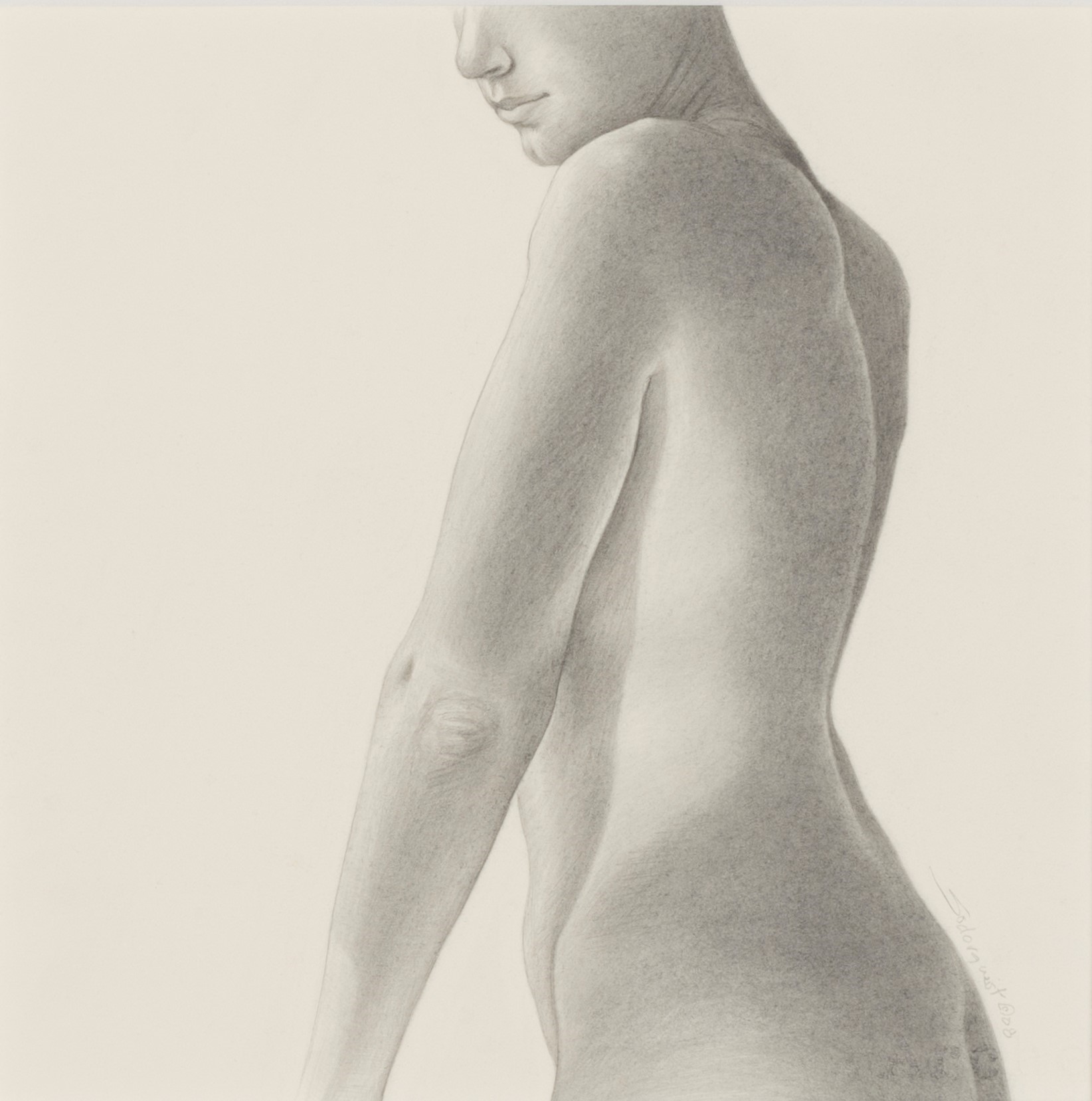

The course load emphasized what Ellen refers to as the “isms,” studying abstraction, expressionism, and minimalism. These influences can be seen in Ellen’s rendering of the figure in the void, using a minimalist background to draw the viewer’s consideration to only the figure and what is being said through the body and its pose.

Ellen received her Bachelor of Science in Art Education from Texas Tech University in 1968. Her portfolio included expressionistic paintings, watercolors, prints, drawings, and a few abstractions and landscapes – but more than anything the nude was the dominant theme throughout her portfolio.

In 1971, Ellen went to Austin to work for the University of Texas. As an employee, she was able to take classes for free, so she signed up for a life drawing class in the UT Art Department. At the same time, she was reading Kenneth Clark’s book, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, and came across the concept that the nude is not just a subject, but is a form of art. These realizations cemented her direction as an artist, and she decided that her art was “the nude”.

Odd Jobs and Influences

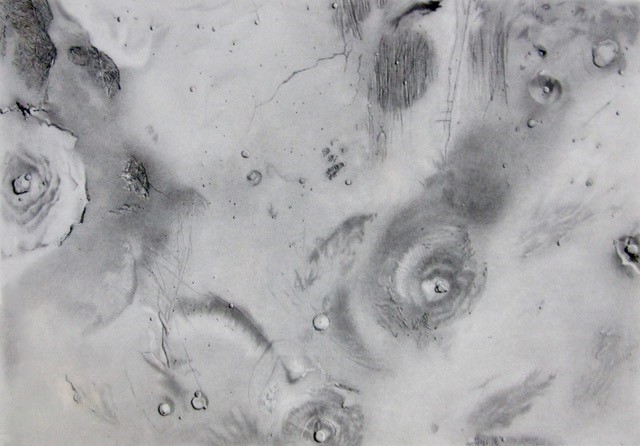

The University of Texas hired Ellen as an illustrator for academic papers and projects. Her first job on campus was working for Gérard de Vaucouleurs in the astronomy department. Ellen was part of a team of artists that worked for NASA through the university to draw maps of Mars under the supervision of Dr. de Vaucouleurs. They worked from the Mariner 9 photographs of Mars’ topography to add in the planet’s albedo, or light and dark markings, with graphite. Their work was published in Sky and Telescope magazine. Ellen’s second job in Austin was working for the Zoology department, making illustrations for the professors’ published articles. For this job she worked in ink on a kind of mylar called Herculene.

Both illustration jobs helped Ellen hone her drawing skills and define her later working practice. While rendering her illustrations of fauna at the Zoology department Ellen became accustomed to working on mylar, and from the Astronomy department she worked with graphite. Drawing extensively with these materials led Ellen to her “particular technique” when she moved to Dallas and became a professional artist.

In 1981 Ellen was awarded a $2,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. With that money, she purchased a drafting table and used the rest to produce a series of three lithographs in collaboration with Texas’ finest fine art print shop at the time, Peregrine Press.

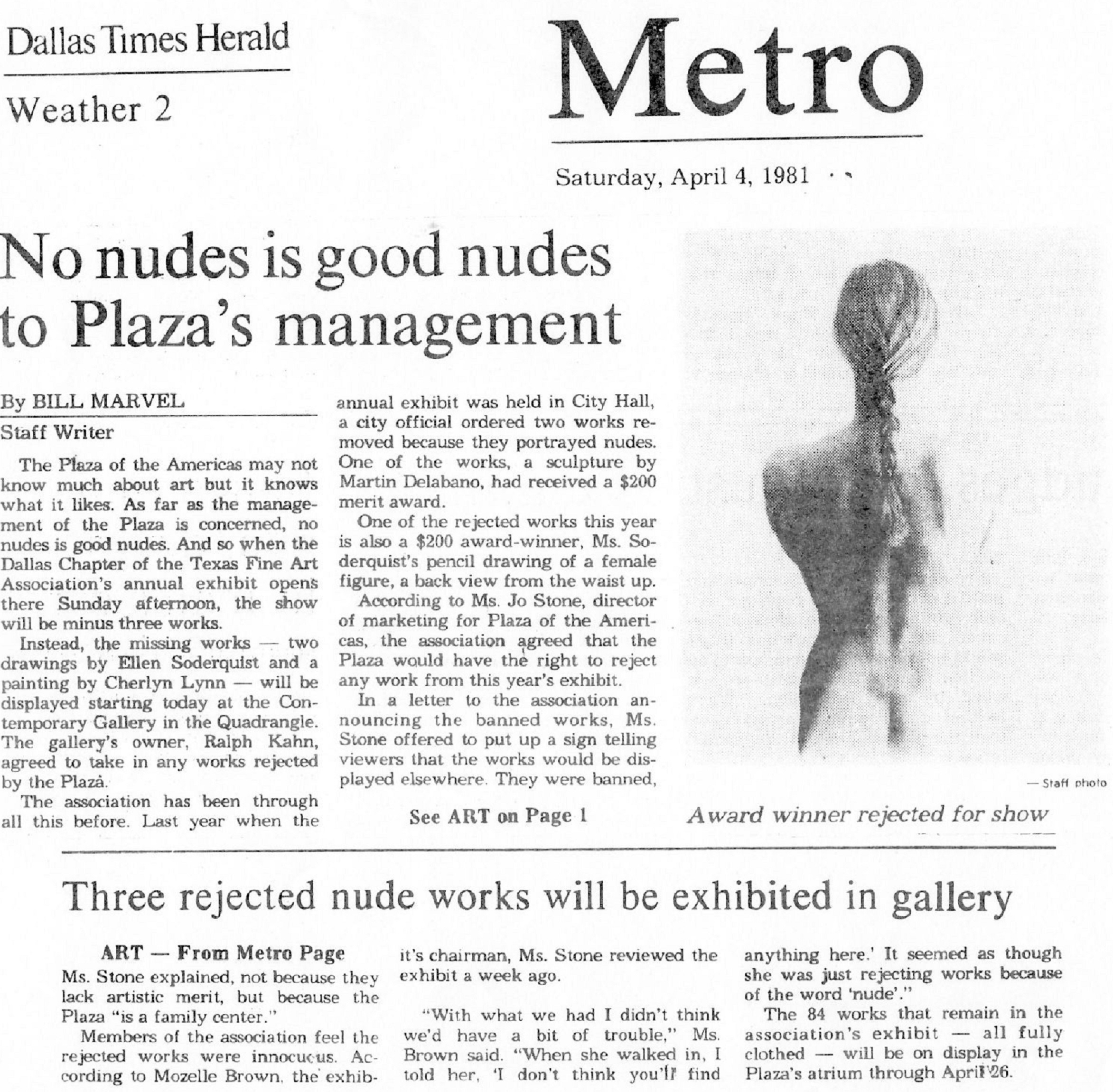

Controversy and Censorship

Ellen knew that her choice of subject matter would occasionally cause controversy. She recalled her first group exhibit at DuBose Gallery in Houston, where she was confronted by a gallery patron who labeled her artwork as pornographic. Ellen said she spent time visiting with the woman explaining what her artwork was about. She was pleased to learn later that the woman had purchased one of her drawings.

In 1981, Ellen was surprised that one of her works was removed from an exhibition at the Plaza of the Americas, an office building in downtown Dallas. The show’s sponsor, The Texas Fine Art Association, had awarded the work second prize. One of the people in charge of the building decided to exclude five works from the exhibit, including Ellen’s, saying that they were inappropriate for public view. Ralph Kahn, a Dallas dealer who was known to not shy away from controversy, offered to exhibit the five “inappropriate” works in his gallery. Bill Marvel, art critic for the Dallas Times Herold, wrote an article about the incident titled, “No Nudes is Good Nudes.”

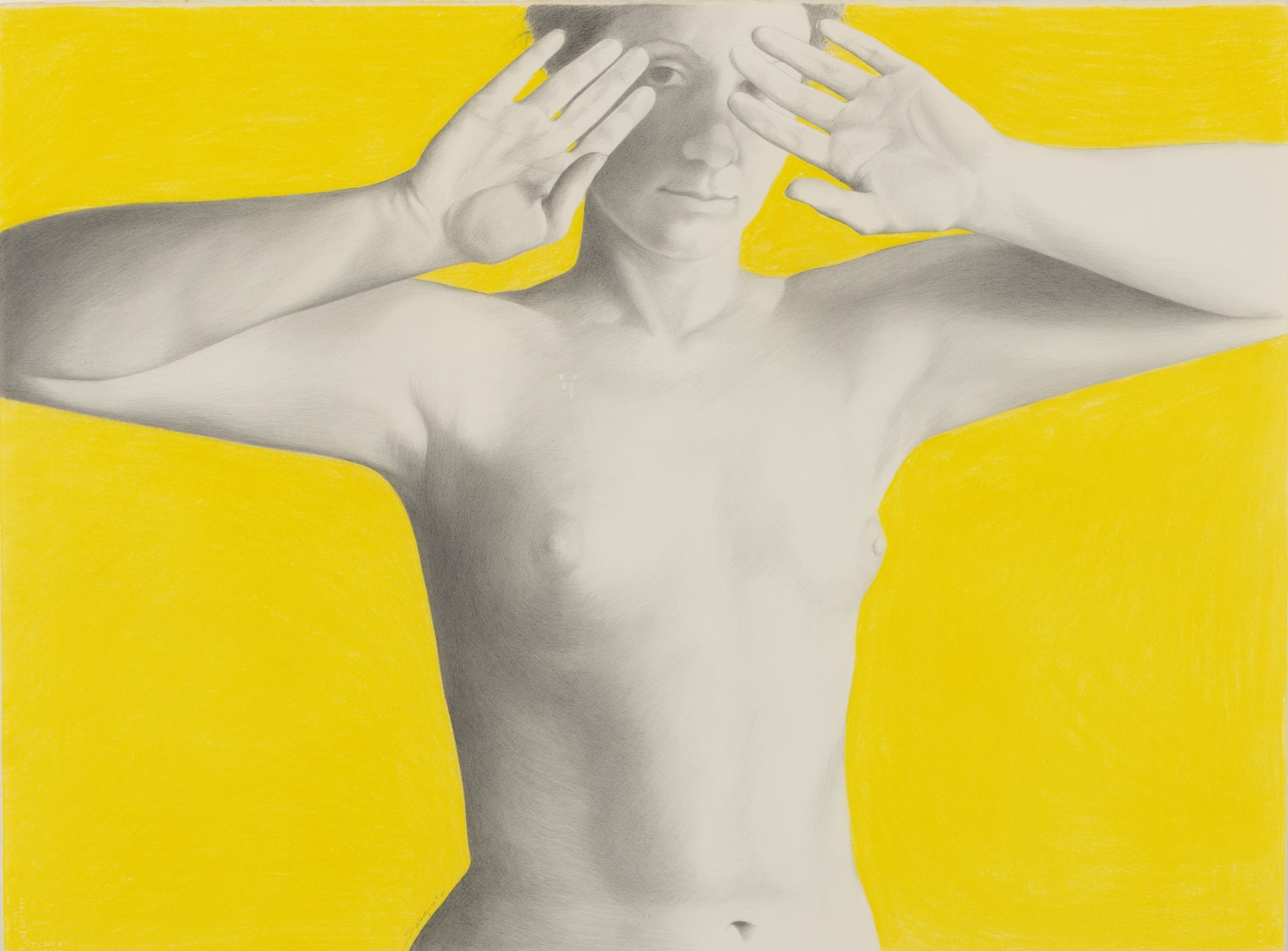

Ellen believes that people who react to her work in this way do not understand her intention. She wants “the graphite to feel like flesh on the surface of the mylar.” She wants the gesture to convey the figure’s inner spirit to the viewer.

An Artist’s Voice

These encounters deeply affected Ellen. She wants her figures to communicate a sense of strength, intellect, and capability. The critiques that she is most pleased with describe her figures as “intelligent, sensual, highly developed, elegant, and provocative.” She has examined attitudes about the nude throughout the history of art and sees this art form as a means of “understanding our humanity.”

In numerous series of artwork, Ellen has pursued a conceptual itinerary that spans the gamut of human emotions and relationships and she has explored contemporary attitudes about the nude as well as those of other cultures throughout the history of art. She strives to bring the complex relevance of the unclothed human body to the consciousness of contemporary culture.

*****

Available artworks by Ellen Soderquist on FAE

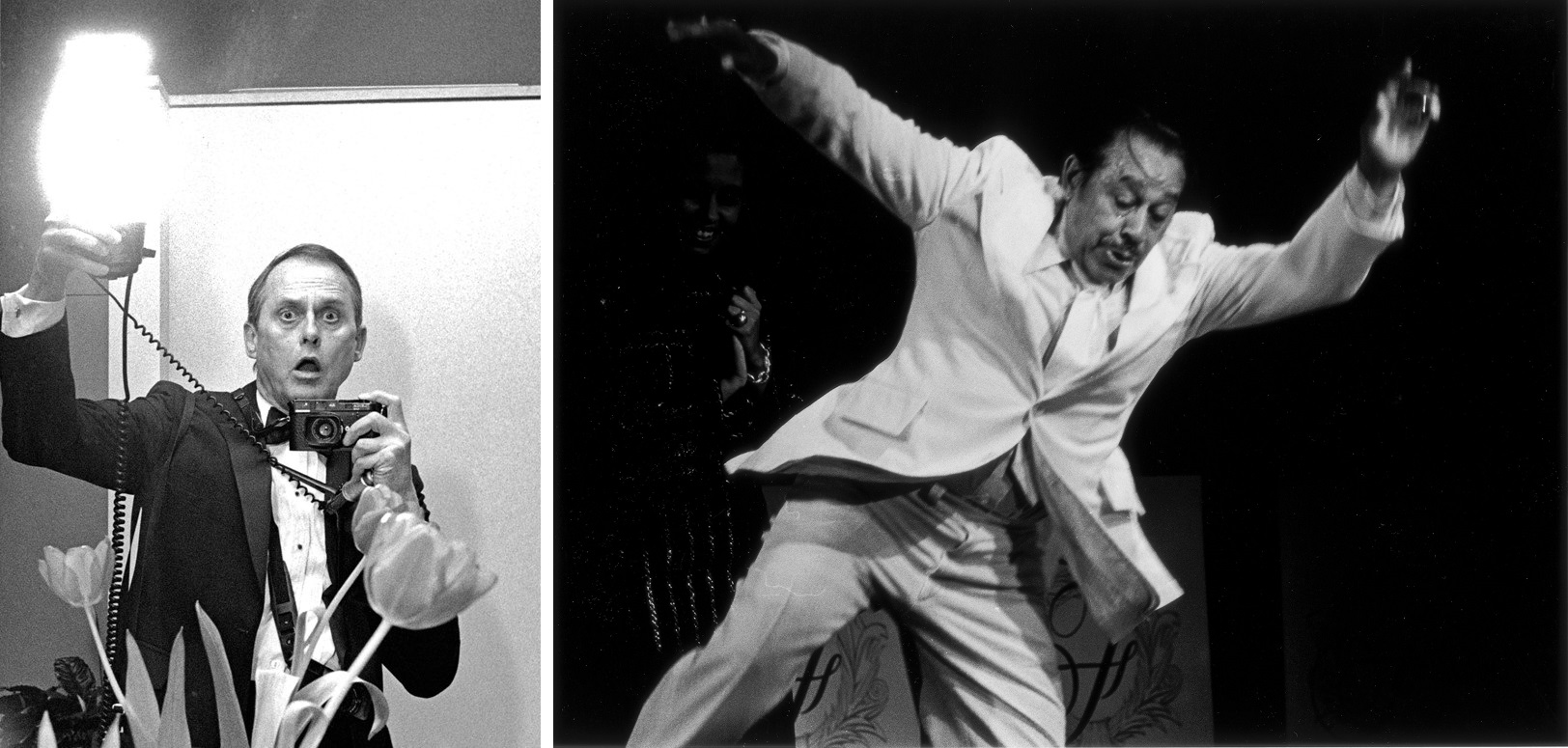

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

OTIS HUBAND: A Consummate Artist

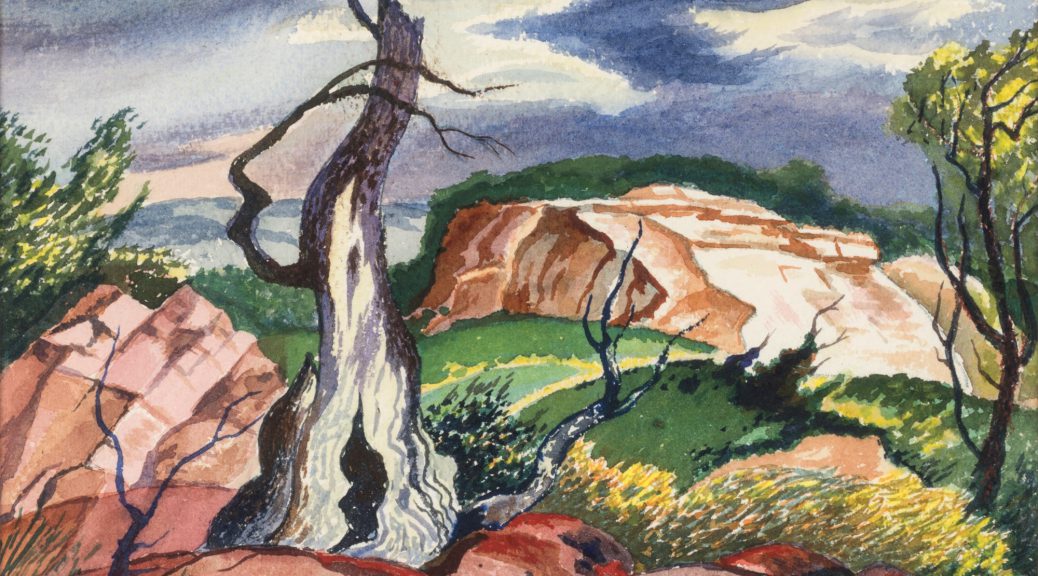

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Dallas Painter WILLIAM ELLIOTT (1909-2001)

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

Three Important Early Paintings by VALTON TYLER

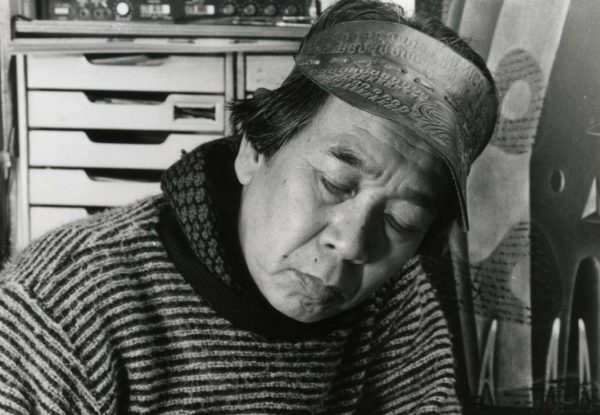

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

YUKIO FUKAZAWA: Master Printmaker

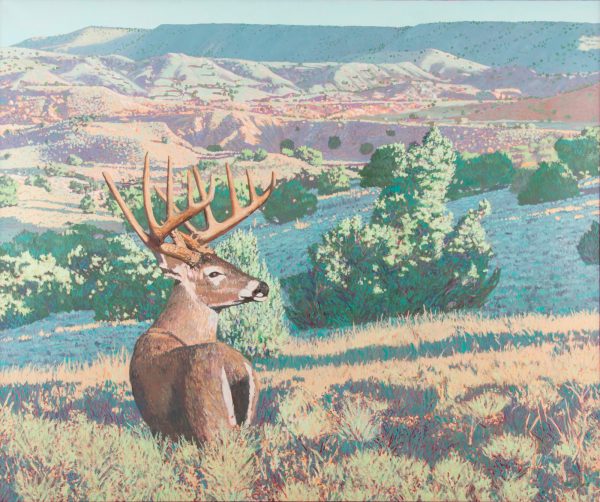

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

Early Career Paintings by JIM STOKER: The Eternal Naturalist

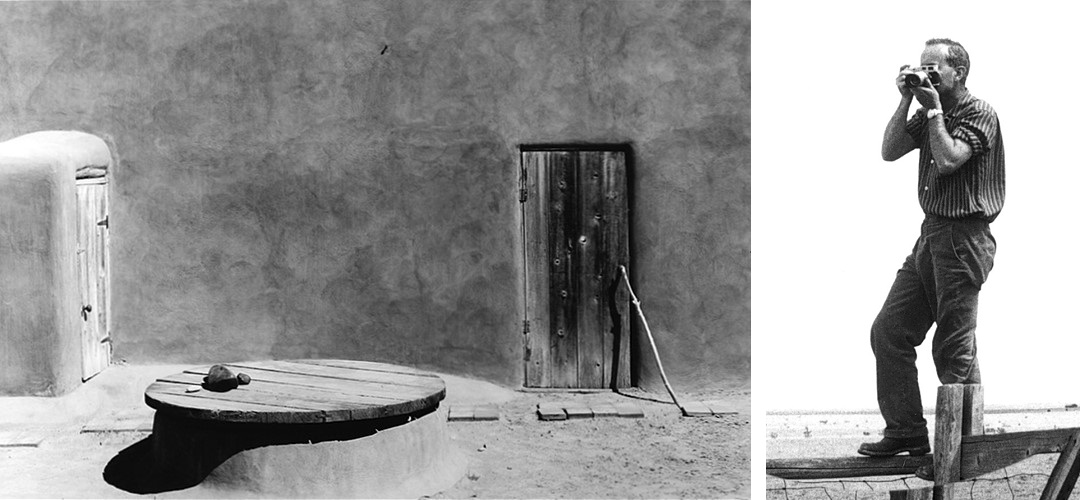

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

Drawings from the Estate of EVERETT FRANKLIN SPRUCE: Texas’ Most Celebrated Modernist

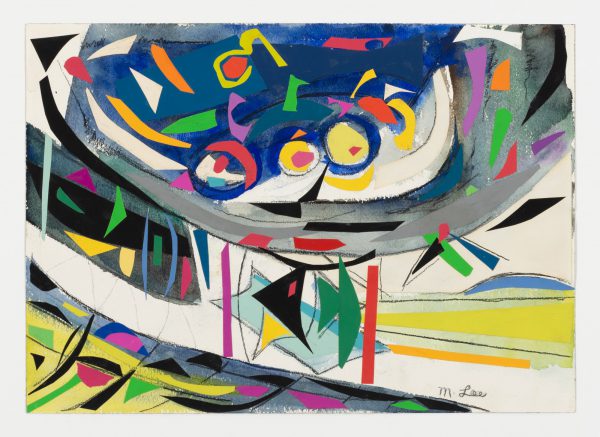

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

MARJORIE JOHNSON LEE, An American Modernist

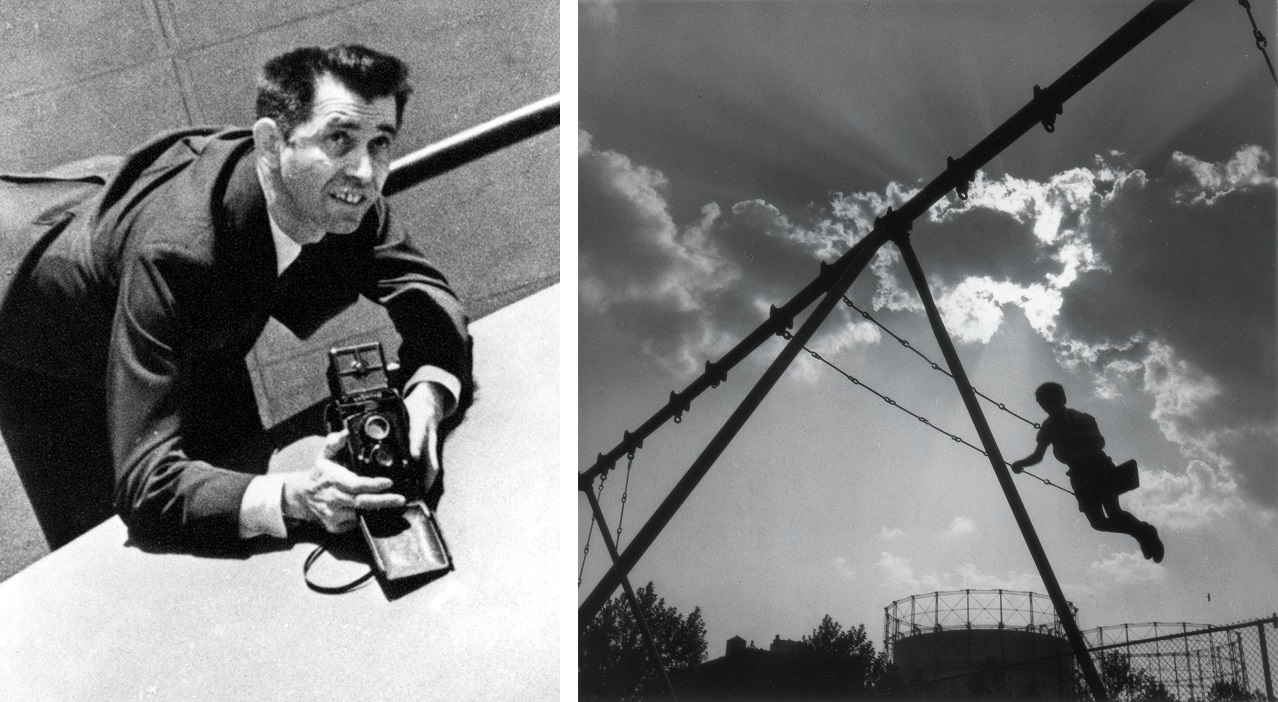

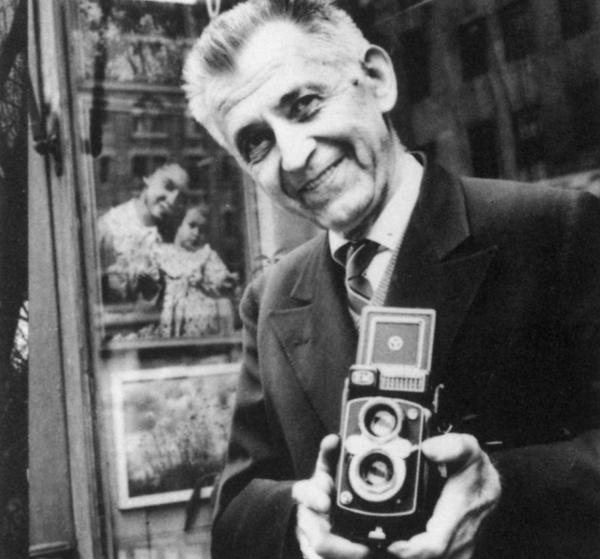

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

Introduction to the photographs of JOHN ALBOK, Part II: the Photographic Archives Collection

To see all available FAE Collector Blog Posts, jump to the Collector Blog Table of Contents.

To see all available FAE Design Blog Posts, jump to the Design Blog Table of Contents.

Sign up with FAE to receive our newsletter, and never miss a new blog post or update!

Browse fine artworks available to purchase on FAE. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter to stay updated about FAE and new blog posts.

For comments about this blog or suggestions for a future post, contact Kevin at [email protected].